Melvyn Penn

Who is the Visitor?

We are going to build a visitor profile from our quantitative data to establish the type of visitor that Tintagel receives. The significance of understanding the visitor is that “any tourism strategy …must respond to the known behaviour patterns or segments of people who visit specific destinations” (Middleton and Hawkins, 1998) [go to references]. It will also provide an important framework for the qualitative information that follows.

The age of the visitor can give us some clues about their expectations of Tintagel. Table 5.1 presents the age of the visitor in ten year cohorts. We can see that the most common age group is between 31 and 40, accounting for 10 of the 27 respondents who were interviewed. In a study of visitor experiences at Lands End, Ireland(1990) found the 30-40 age group to be the most sensitive to an increase in visitor numbers and this would suggest that visitors come to Tintagel at this time of year in search of solitude.

We should like to establish to what extent Tintagel does fit into the romantic scene. Earlier, in the introduction, we saw that the romantic gaze is likely to be enjoyed in solitude (Urry, 1990). If visitors to Tintagel at this time of year are sensitive to the presence of others, we could expect to find small visitor groups.

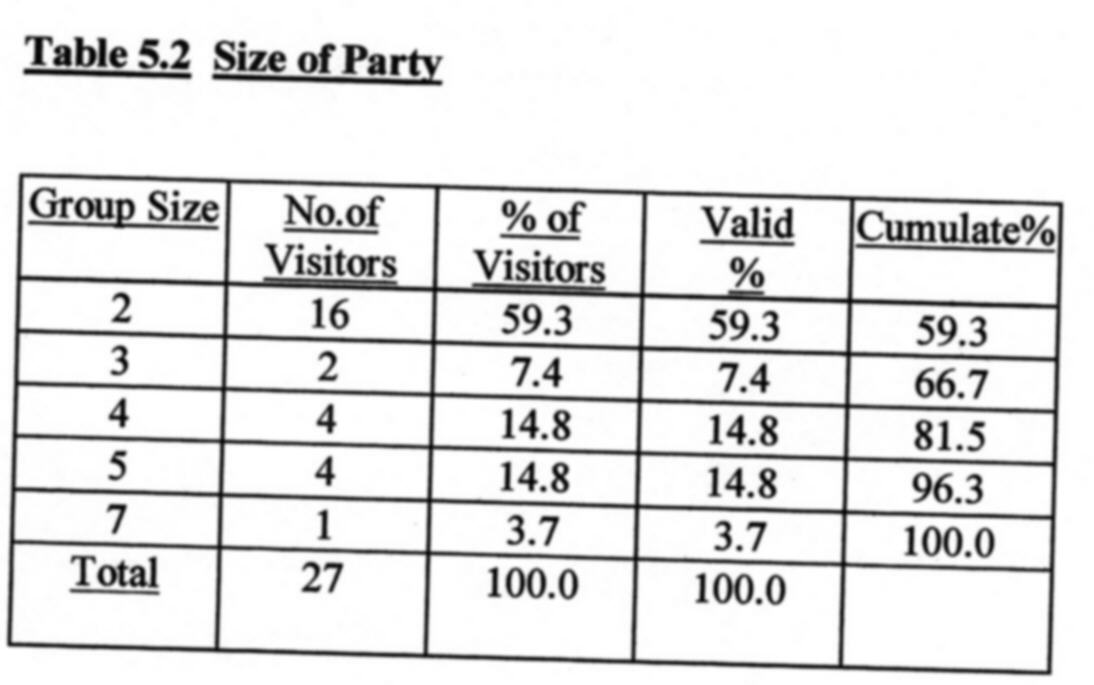

Table 5.2 shows that 16 of the 27 respondent chose to experience Tintagel in groups of only two people and this would tend to confirm that the tourist quest at Tintagel is for romanticism and solitude. We could expect any tourism strategy to increase visitor numbers to Tintagel to be sympathetic to the physical and social carrying capacities. This is not so straightforward, given Tintagel's poor economic status. It's economy is particularly dependant on the tourism sector, calculated at 30.8% in 1991 compared with 23.6% for the rest of North Cornwall (Tintagel Regeneration Forum et al, 1998). The new planning proposals of the Tintagel Enhancement and Regeneration Project must operate within a fragile environment where cultural capital and real income can all too easily compete.

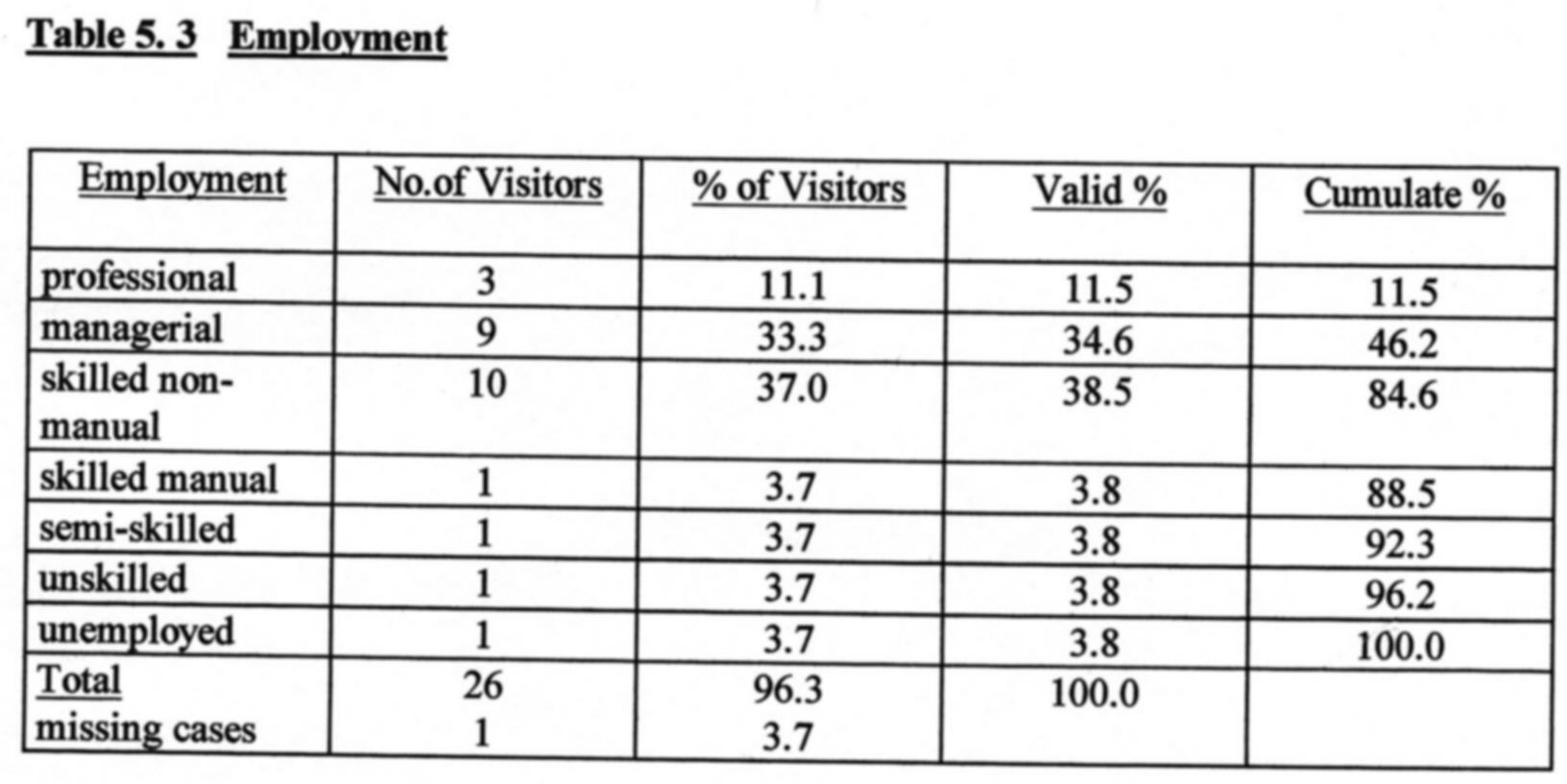

In research methods we saw that the locals perceived the visitor at this time of year to be rather affluent. Table 5.3 would tend to confirm this consensus. We can see that from the 26 respondents, 22 of them are employed in non-manual labour. Personal interviews with the service sector at Tintagel revealed that the affluent visitor is held in high regard. An example of this is the loathing of the Ocean Cove caravan centre for attracting the wrong kind of people in summer. One employee, speaking of the caravan park, said that Tintagel is not the place for the ‘bucket and spade brigade’. This indicates that locals are likely to act more favorably towards visitors at this time of year and good customer care can enhance the visitor experience. Curiously, the Tintagel Enhancement and Regeneration Project (Tintagel Regeneration Forum et al, 1998:1) appear to give little consideration to the types of visitors they aim to attract.. In their bid to “restore an image of Tintagel as a top quality and unique visitor destination” there is, on the contrary, “a pressing need…to broaden its appeal to a wider cross-section of visitors”. Hostility between locals and visitors may do little to enhance Tintagel’s image.

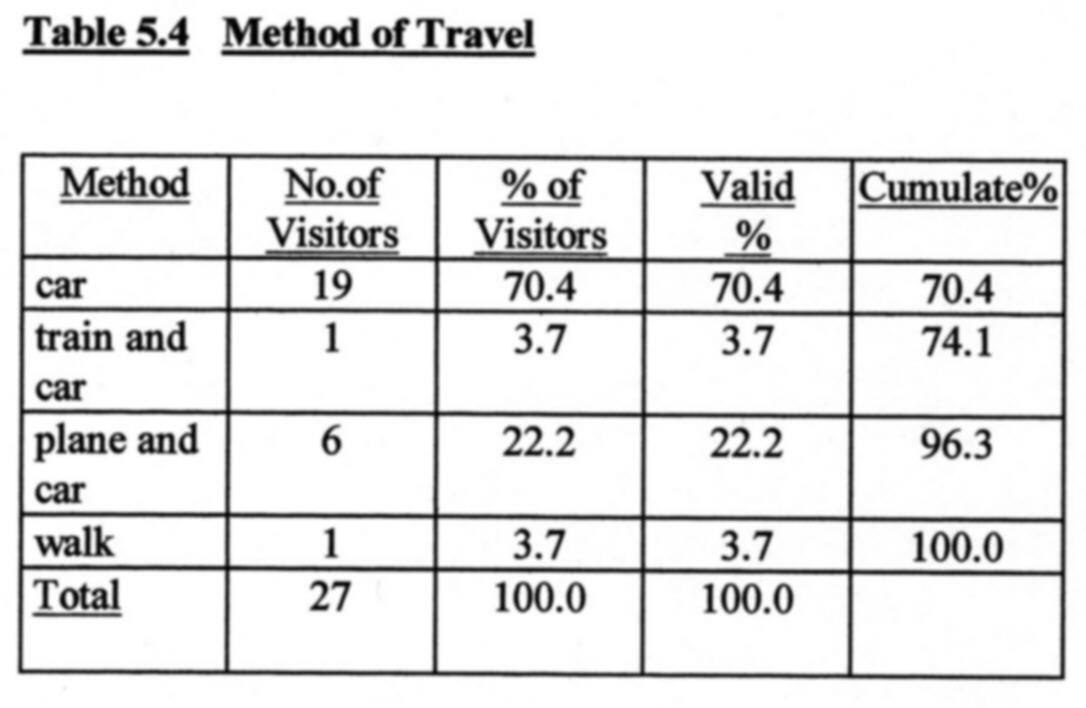

Having learnt that the visitor to Tintagel at this time of year is likely to be fairly affluent, can we expect them to travel here by car? We can see from table 5.4 that 19 of the 27 parties interviewed travelled to Tintagel by car alone and that a further 7 used the car in conjunction with other forms of transport. The car was only excluded altogether from an itinerary by one respondent!

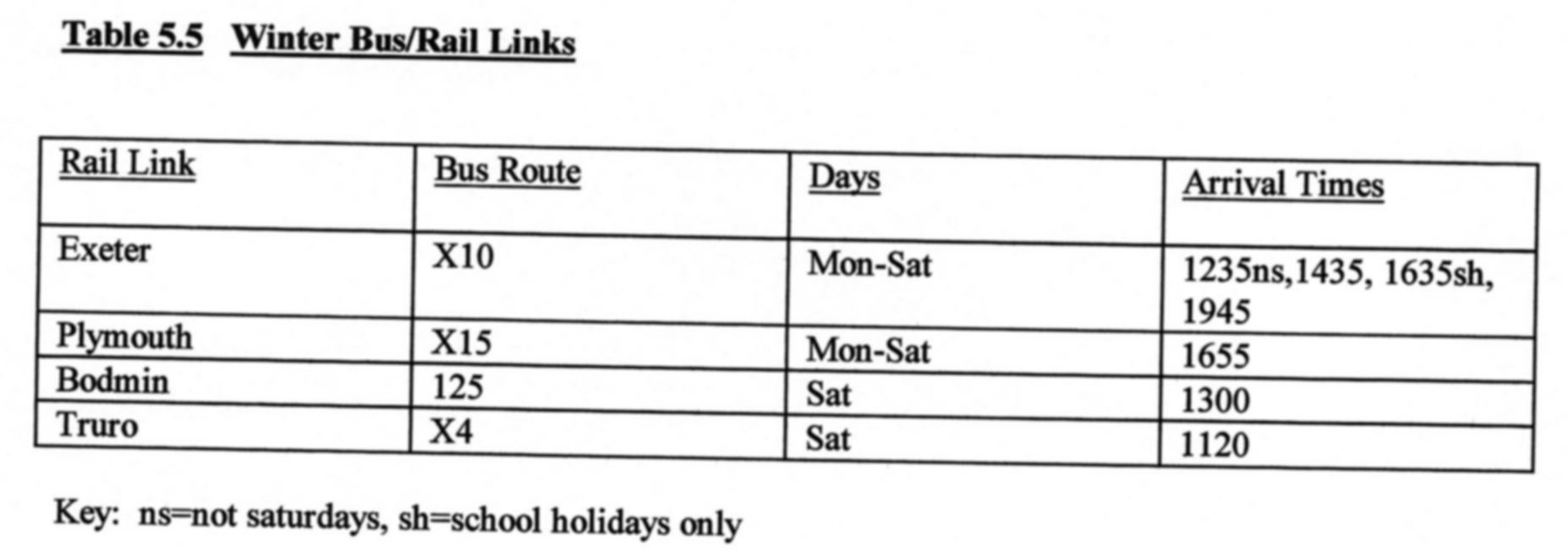

An interesting observation of the service class (white collar worker) by Urry (1990:99) is that although they will be wealthy enough to own a car they will be willing to use environmentally friendly forms of transport such as coach or train. This prompts an investigation of public transport opportunities at Tintagel at this time of year. There is no railway here and, according to the North Cornwall winter bus timetable (1999), the only direct bus/rail connections serving Tintagel are with Bodmin, Exeter, Truro and Plymouth. Table 5.5 shows the arrival times of these bus routes at Tintagel.

The restrictive nature of these bus

routes speak for themselves and their departure times or connecting rail

times have not even been included. Visitors who wish to come

to Tintagel by public transport during the winter timetable are therefore

required to construct complex itineraries and this is hardly an attractive

proposition. Public transport is often perceived as an environmentally

friendly alternative to car travel and this is congruent with Tintagel’s

romantic image. An improved winter service could help to disperse

visitors throughout the year and to generate a regular flow of tourist

income.

Even when travelling by car, Tintagel is not always an easy place to reach. It is worth recalling that Tintagel is located in the extreme south west of England and visitors who reside from outside of the West Country will be required to travel for long distances to reach it.

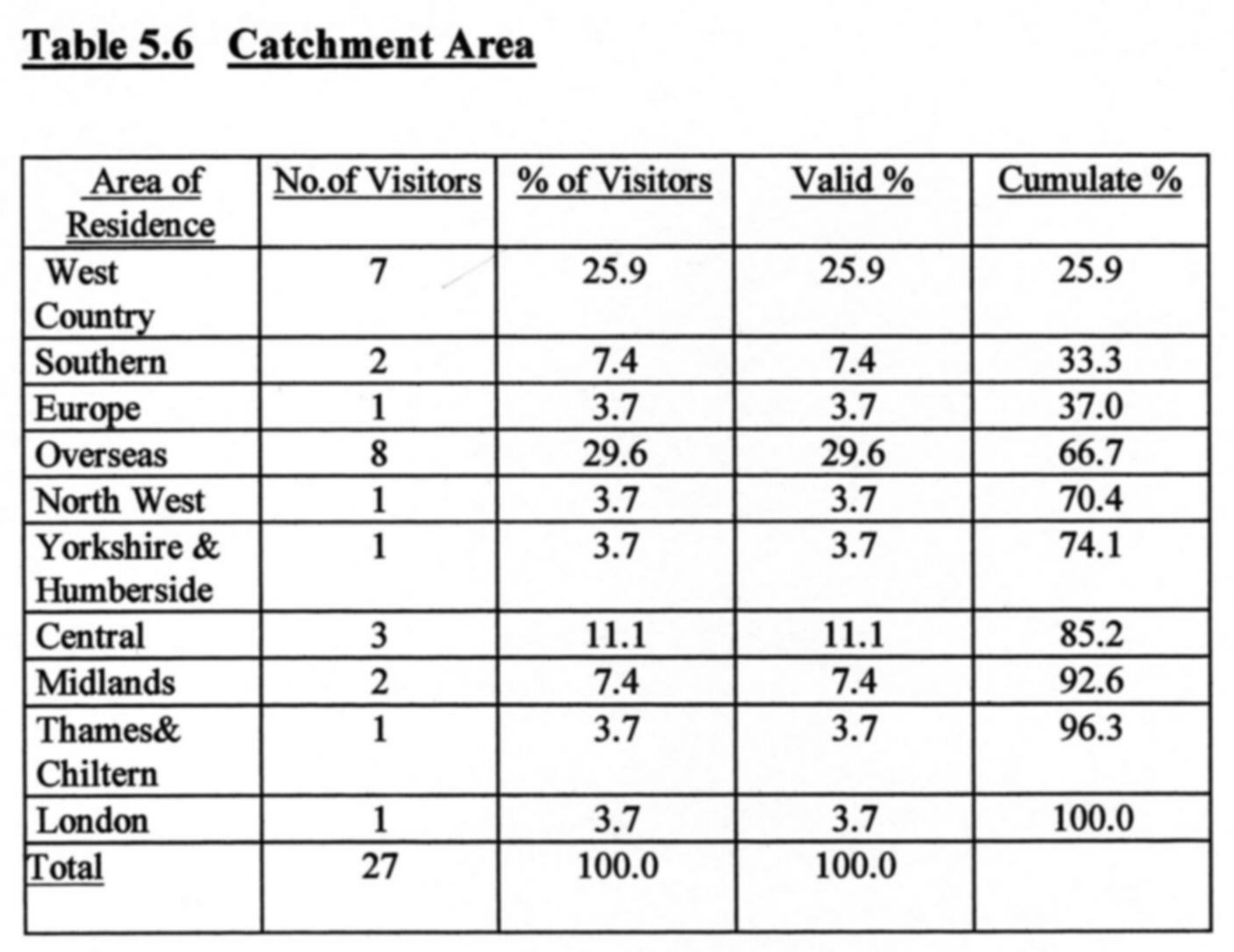

Table 5.6 reveals quite an array

of visitor catchment areas. We could expect to find a large number

of visitors from the West Country and this sector accounts for 7 of the

27 respondents. In contrast, it is encouraging to see that a large

proportion of visitors have travelled from overseas. This information

is all very well but it does not tell us very much about how these visitors

behave in Tintagel and how they utilise their time.

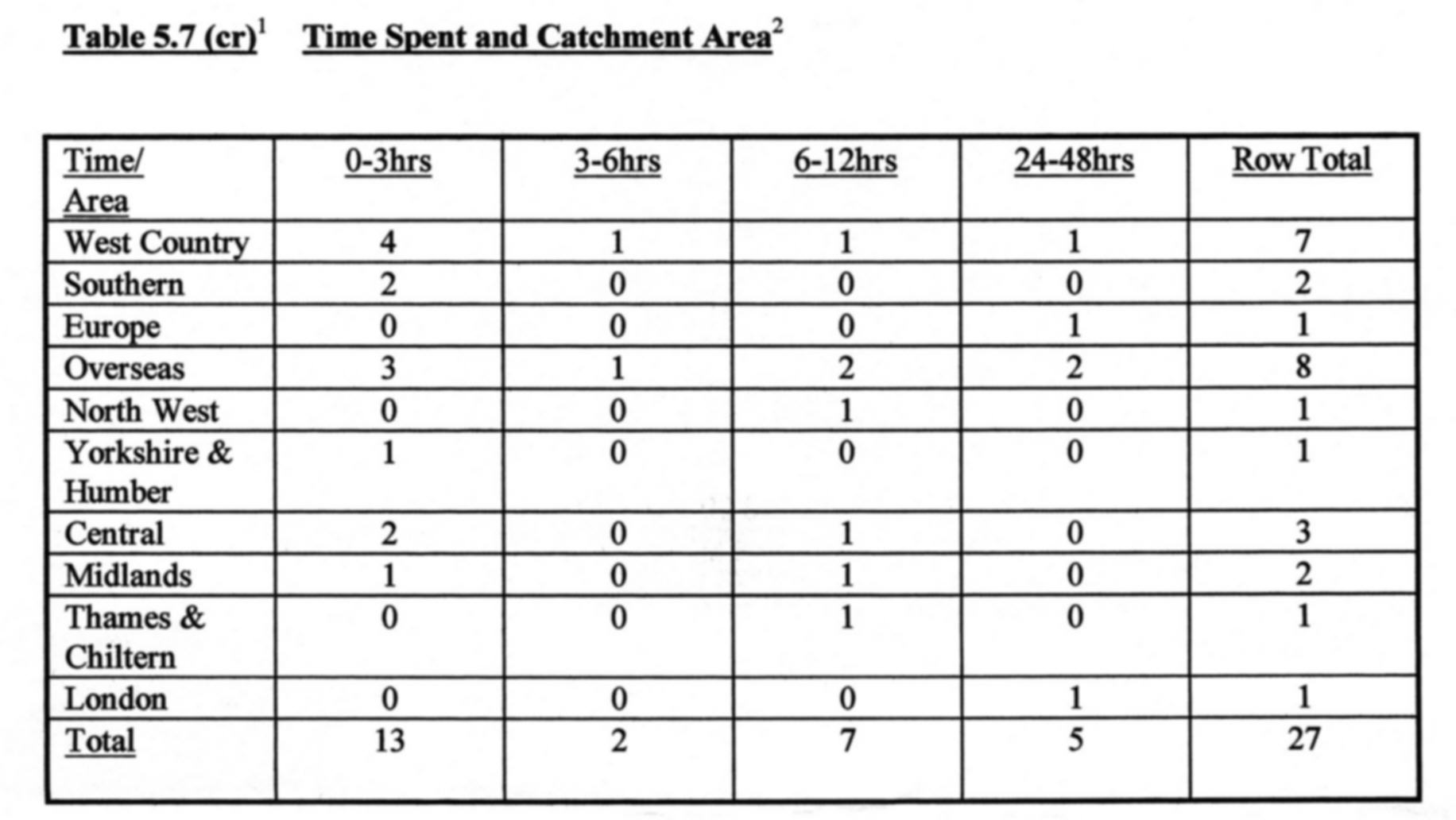

1 -- cr = crosstabulation,

comparing statistics for two or more variables

2 -- Time spent has been

calculated by combining duration of present visit

with intended to stay.

See also coding in appendix

Table 5.7 examines the relationship

between the two variables, catchment area and time spent, and tells a rather

more melancholic story. Once again, considering the proximity of

Tintagel to West Country visitors, we might expect it to appeal to them

as a short-break destination. It can be seen that 4 of the

7 respondents in this category spent between 0-3hrs at Tintagel while only

one stayed overnight. However, visitors from further afield also

found difficulty in spending longer than 24hrs at Tintagel. Only

2 of the 8 overseas respondents stayed overnight while 3 of these respondents

only stayed at Tintagel between 0-3hrs. And those from the north

of England, who in a sense may have travelled further, only stayed between

6-12hrs (North West) and 0-3hrs (Yorkshire).

.

When we consider that the average

length of stay for visitors to North Cornwall is 7 days for domestic visitors

and 8 days for overseas visitors (North Cornwall District Council, 1998)

this is obviously of some concern. “You cannot do Tintagel in an

afternoon or a day” suggest Young & Williams (1994:6), and Boney (1959)

recommends various itineraries for spending a week or two. Visitors

who merely pass through Tintagel are therefore likely to form unrealistic

impressions, particularly, as we have seen, when fragmented experiences

are consumed.

It is a concern that has not gone unnoticed in the Tintagel Enhancement and Regeneration Project (Tintagel Regeneration Forum et al, 1998). Encouraging visitors to spend a longer time in Tintagel is one of their main objectives. The new proposals are expected to attract a further 7,500 staying visitors per year, which is expected to generate an additional expenditure of £258,750 into the area. We have seen, however, that one must be careful when planning for rural destinations in terms of quantifiable measures. While it would seem logical to increase the length of stay during off-peak periods this could be detrimental to the visitor experience during the summer months.

The distinction between seasonal periods in the marketing and planning of Tintagel is rather enigmatic. Personal interviews with tourist professionals revealed a concensus that Tintagel is already promoted enough. This ethos would appear to be justified from our semiotic analysis of Tintagel. Consequently, Tintagel only appears under a small section on King Arthur in the 'North Cornwall 2000' brochure (North Cornwall District Council, 2000).

We might propose that there are occasions when a destination actually needs to be promoted in more detail. Winter time at Tintagel would appear to be one of them. Off-peak promotion in the brochure is confined to a double page, entitled 'North Cornwall all year round' (2000:20), where we are requested to look for the bargain prices in the accommodation section. Such an integrative approach between tourist establishments may be the key to visitor dispersion but should ideally involve varying degrees of marketing. A separate winter brochure, for example, could promote price concessions and seasonal appeal at Tintagel much more effectively.

Finally, we introduce an important variable before moving on to address more qualitative issues. When we looked at anticipating the experience we saw how Tintagel could act as a marker per se. Visitors were then asked whether they have previously visited Tintagel before as this could clearly influence their expectations. Table 5.8 reveals that twice as many respondents (18) were engaged in a repeat visit than those who had never previously been to Tintagel. Are repeat visitors then likely to behave differently to those who are visiting for the first time? This issue is addressed in table 5.9, which examines the relationship between repeat visitors and the duration of the visit at Tintagel.

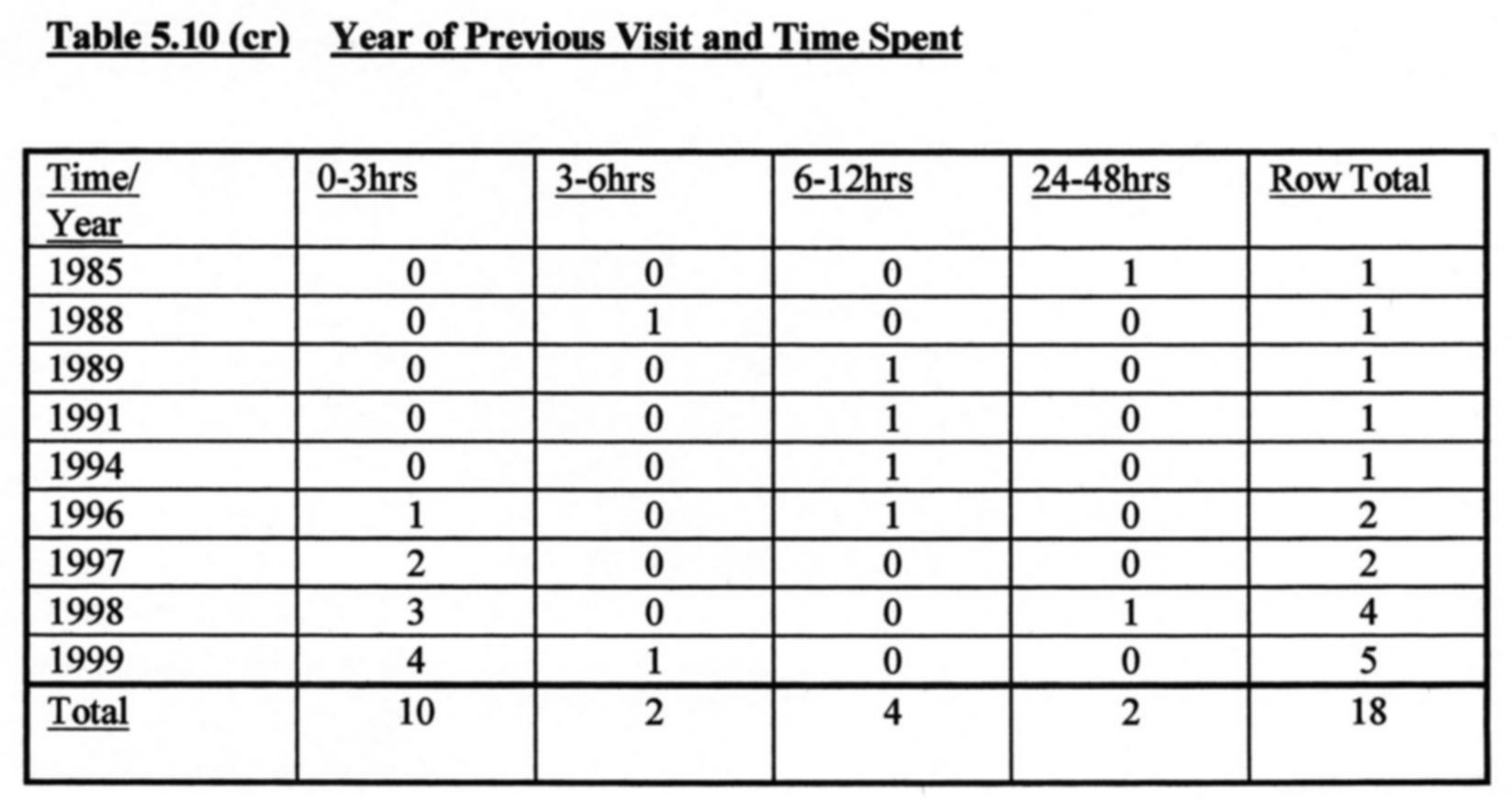

We can see that 10 of the 18 respondents who had previously visited Tintagel only stayed between 0-3hrs on their present visit, while those who were visiting for the first time generally stayed for longer. Is this behaviour normative, or could it indicate that the markers exceed the visitor experience? One further issue is pertinent in establishing Tintagel’s status as a marker. Those who were making a return visit to Tintagel were asked to recall when they had previously visited. These responses have been crosstabulated with the duration of their present visit to see whether this will influence the amount of time they spend here.

There are some interesting patterns of behaviour emerging here. Previous visit decreases proportionally with time spent. Those respondents who had most recently visited Tintagel were prone to make a return visit but generally stayed for a short length of time. To illustrate this point, we can see from table 5.10 that half of the eighteen (9) respondents had visited within the last two years (1998-99) and 7 of these only stayed between 0-3hrs on their present visit. It is rather difficult to account for these conflicting patterns of behaviour at this stage. A possible explanation is that repeat visitors may then be attracted to selected sights based on previous experience.