| Notes on: Iesha

Jackson, Doris L. Watson, Claytee D. White and

Marcia Gallo (2022) Research as (re)vision: laying

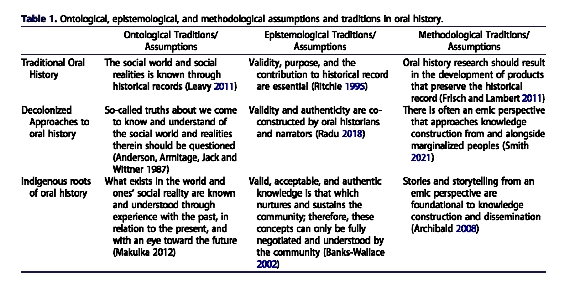

claim to oral history as a just-us research methodology. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH & METHOD IN EDUCATION 2022, VOL. 45, NO. 4, 330–342 https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2022.2076827 Dave Harris They wanted to do some oral history with three Black and Latinx schoolteachers to see how they navigated racial micro-aggressions and everyday challenges, but their local IRB said it wasn't proper research, despite oral history being defended in the literature. The US generally deems oral history not to be scholarly enough, so they proceeded anyway, after critically reflecting on what counts as research, which was taxing. They 'refused to accept' that their approach was 'somehow less worthy or rigourous' and began to recreate an approach to research 'in community (330)', reclaiming the power within their own multiple identities which include Black Indigenous People of Colour (BIPOC), women, queer and scholars. They recalculated their own depth of understanding of colonised Western research practices that had rendered their knowledge as inferior or invalid and in the process recaptured what it is that they knew and had forgotten. That new understanding formed the methodology of their research. They located themselves in the new complexity of creative qualitative research, something culturally informed and critical, challenging, and reforming taken for granted norms. Researchers could no longer be the primary instrument for data collection, nor searching for patterns as the primary tool for making meaning. They wanted to include 'embracing the resonances of our souls' (331), and align with indigenous traditions and their abilities to create a community in which they understood each other. They call this a 'just – us' methodology. They analyse indigenous roots of oral history and revised conventional research methods. They drew on Dillard and Bell to understand the process as '"situated, sacred and spiritual work that happens in multiple spaces and places where African ascendants and other indigenous peoples find ourselves"'. The vision and practice of such research is healing and racially just. Oral history is briefly reviewed, and much of it lies outside of the IRB purview. It can be seen as a 'co-optation of indigenous oral traditions'. They want to reclaim storytelling in particular. They summarise the different approaches in a nice table [eventually]. There are differences of ontology, epistemology and methodology.  Traditional oral history is usually divided into usable versus useless oral history depending on contribution to historical records based on missing voices. Useless oral history is often one in which the interviewer was unprepared and therefore does not collect meaningful information or where research is not designed to contribute to the historical record. As a result it's usual to outline essential purposes — to fill in the historical record, understand people's experience of historical events, contribute to the understanding of specific topics, gain community knowledge. Others have tried to tidy up oral history by suggesting a division between the raw materials like conducting and transcribing interviews and classifying the products that result. Still further commentaries discuss ways in which narrative was studied and understood within academic circles, say in terms of the academic disciplines: sometimes this has challenged colonial projects. There has been a decolonised approach. Feminist scholars in particular have challenged the validity of conventional oral history and amplified the voices of females, arguing that women should speak for themselves to reveal their own realities. Indigenous methods do the same, with an awareness that colonial and epistemological hierarchies can be perpetuated, and as an alternative, requiring '"intimate reciprocal relations with storytellers and community partners"' (333), or maintaining '"clear and culturally specific responsibilities to the collective"'. Additional requirements may also be necessary to avoid whitewashing indigenous ways of knowing. It may be important to produce work 'that honours the collective even if it is rejected within the Academy'. It is common to find academic sources describing oral traditions as prehistoric earlier endeavours preceding proper academic oral history, such as the work of African storytellers. As a result, gestures, intonation and context are often omitted in oral performances, together with traditional elements as well as personal memories. 'The concern with authenticity, accuracy and/or validity of oral tradition… Is mediated by oral history' or alternatively historical memory is preserved to connect present generations to the past, to 'allow communal knowledge to proliferate'. Indigenous people might claim to remember at need rather than being fixated '"on elites and archives"'. Oral history often has indigenous roots. Scholars visiting places they did not originate from often created 'for themselves a whitewashed version of indigenous practices' (334). This is to be contrasted with indigenous people who 'broadly… are original to their homelands'. A Maori example is provided — individuals do not see themselves as separate from their oral history and traditions. Banks – Wallace claims that storytelling in the African-American oral tradition is about healing and nurturing, '"through communion with The Spirit"', that the sharing of stories is sacred work, and that has played a '"critical role in the survival of African-Americans"'. It is 'part of who we are as BIPOC', and an accepted research method in producing products that are disseminated through our communities. Indigenous elders have various knowledges that they share as they are passed through 'story work' which includes education and research work, making meaning. This is not 'recounting fantasy or fiction or even publicly performing stories as entertainment' but more a matter of being able to 'reclaim the events containing accurate, factual data from memories, feelings and facts spoken by narrators or storytellers' [which rather contradicts what was said before] it also includes 'several ethical considerations' including '"being intellectually, emotionally, physically and spiritually ready to fully absorb cultural knowledge"… Reciprocity… Benefit to the community, maintaining trust… Listening with your whole being or collecting stories in a manner that is as spiritual and emotional as it is intellectual and physical' (334 – 5). It is teaching through 'codified (even if only tacitly) practices'. Usually, however we've not been allowed to define this outside the boundaries of white academic norms so we ought to reclaim it as originators of oral history [originators maybe, but is this the best form of oral history? Should be sticking with the original form?]. Dillard reminds us that teaching and research both involve memory and remembering, and in their case remembering means referring back to the literature and the storing of themselves. There is also a part of consciousness that does not rely on words it is 'spiritual in nature', according to Dillard again involving consciousness, choosing 'to be in relationship with the divine power of all things' (335). They chose this to connect with things beyond their intellect, in order to further go beyond the 'scientification of oral history'. There were led by a consciousness or inner knowing 'that called us to this work' they felt obliged to highlight the racial injustice of being erased. They sought language that attempted to unmask these traditionally held political and cultural constructions and depressions and that led them to re-vision research methodology. The result is a 'unique application of interviews feelings and facts that expands critical thinking, storytelling dialogues that enrich teaching and learning. There is no model for their project, although it is not completely new — 'it is a reconstruction based on salvaging and reforming fractured pieces of our indigenous selves and histories'. They see it as a matter of surrendering and highlighting healing potential, aligning with their own cultural ways of knowing and being. Each author provides their own story of how they became a researcher tapping into indigenous oral traditions and cultivating a liberatory process helping them theorise research as ReVision. Marcio Gallo: disrupting narratives She was inspired to work with the Collective and reaffirm its significance, to share the 'unvarnished truths of our lives' (336) which also involved 'learning to unlearn'. She is an historian of LGBTQ social movements and she knows that personal narratives are crucial especially when archives do not provide much evidence of such people. Both oral history and lesbian and gay history were animated by the same imperative to interpret marginalised subjects and their histories. She began by researching the first US lesbian organisation the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), a pre-Stonewall group. Archives were limited so oral history became a necessity. Using a snowball method, she contacted 35 women and men and interviewed them multiple times. She encountered questions of race and racial silences in these histories, for example the eight original founders included 2 WOC, a Filipina and a Chicana, as well as one young blind black person. The significance of black and brown women emerged in other oral histories, including one who urged the adoption of civil rights movement tactics, and the original founder of a magazine. The revitalising potential of oral history was clear and has been carried on in their current 'just – us' work that disrupts 'previously all-white narratives'. Doris L Watson (re-) remembering my way back She returned to faculty after a three-year stint as Associate Dean just as Covid 19 emerged. Her spiritual self was reawakened and she invoked practices of walking meditation in her own spiritual practices [attributed to a certain Thich Nhat Nanh], which engendered peace and serenity, it involves walking in a childlike manner 'i.e. playfully' [and rather mindfully 'letting go of to get somewhere and just be']. She let go of and re-engage scholars she'd read many years before include bell hooks, Paolo Freire and Cynthia Dillard. She re-engaged with teachers of colour and the group that became to be known as The Collective, a cross disciplinary team, which encouraged her to let go of what she thought she knew. She was not 'intimidated by the magic we conjure as BIPOC scholars and leaders' (337). In conventional qualitative research, we are taught to consider ontology, epistemology, axiology ['what is the role of values'], rhetorical [values] 'what is the language of research', and methodological. She finds this conventional training 'most inauspicious' instructed to 'know and thereby control the world rather than allowed to come to know… We have diminished our own ability to hear our stories — the stories that lend to community — to (re-) remembering' She's been transformed, provided with the gift of immersion in her local community, able to hear and learn of lived experiences. She is now been able to challenge academically acceptable definitions of knowledge and ReVision her own philosophical assumptions the community has been the research method enabling participants to remember themselves to research 'who we were, who we have forgotten' [in other words, a collective therapy after management] Claytee D White: speaking our own truths She was a non-traditional graduate student in history who undertook oral history training. She was initially 'scared and excited' and began with an interview with a couple talking about the 1920s in Las Vegas. She added various other projects from different communities occupations and ethnic groups. Eventually she looked at white supremacy in a particular county school district. She went on to examine women in gaming and entertainment, and found that all the work so far had been authored by white men, and that much of the earlier history involving black women had been ignored. An early collaborator was a local worker and mother in the community, she provided access to community memories involving stories of historical events which 'went beyond storytelling and became recognised as history, American history' (338). More participants were invited to relate black experience and more people are now telling their own story 'with racial power as racial emancipation and anti-subordination' encouraged by BLM. 'This truth is filtering into the schools' Iesha Jackson: finding myself through (re) revision She reflected on Dillard and Bell referring to 'situated sacred and spiritual elements of the process of research' when black and indigenous people find themselves. She began with traditional academic work, but when the IRB said her project was not research, an unanticipated consequence, put herself on a path to redefining herself as a scholar. She stopped thinking about collecting data and started 'gathering and mending pieces of ourselves to research process that was no longer limited by the confines of an institutional review board' after participation in conversation, 'the boundaries between researcher and researched were obscured' Former students were invited to join the project, 'people with whom I developed affinity' (339) budding educators. The point was to understand the life history, why they chose teaching and how the teacher education program might develop an induction programme will histories were to be a foundation. They were connected with the research team from the beginning and this 'allowed the sacred and spiritual to flow'. Connections went beyond those expected by the role of Professor, into a genuine willingness to share. She inserted herself and her experiences, shared stories, deepened their personal relationships. 'I was not concerned with accuracy, validity, a historical record, or any of the other methodological traditions', although she thought her practice was actually 'more aligned with oral traditions' in that she understood shared stories as part of individual past present and future lives and also simultaneously worked 'to provide mutual healing and nurturing' is that part of the work that helped her 'recognise the sacredness of our process' — she means 'both set apart (outside the bounds of what the institution deems research) and reverently dedicated to ourselves as we created (and still maintain) a community had resorted the way I think about what it means to conduct research. [And beyond criticism in the Durkheim sense?] The project occurred at the time that she was questioning 'my will to remain in the Academy' she was still going through the motions of being a professor but had lost sight of the vision. She was interested in the spiritual aspect of research, affirming her call to teach. This is been reaffirmed. Research itself is now '"nurturing the spirit – self [Banks-Walker] in communion with the divinely orchestrated collection of people who see and understand a greater purpose for a collective work'. This would not have emerged if they'd stuck with traditional research methods. She would have been uncomfortable inside those boundaries. Reclaiming the approach 'was liberatory and life-giving for me' (340). Overall, even though the institution said this was not research, she experienced it as an invitation to theorise and to revise the concept of research, to develop a new conception through indigenous methodologies and methods. These included situating themselves in community, beyond what is normally thought of as ethnography, responding to individuals and the collective through the understanding of 'the Zulu concept ubuntu, commonly translated as "I am because we are" but encapsulating a larger concept of the oneness of humanity"' with our whole beings, evoke Spirit in a way that is not usual in oral history. We do not separate the personal from the professional. We bring our full selves to our work. These make the methods authentic to us 'or "just – us", while also being connected to indigenous roots of gathering and recording data. We saw our research as worthy and legitimate in spite of IRB'[still hurts then]. We suggest that this is a pathway 'for racially just approaches to scholarship with/as Black and Latinx peoples'. We want to create an academic life '"that resonates with spirit" to centre that life around community, something integral to socialisation knowledge construction and the preservation of history. We confront erasure co-optation and scientification and do not see the future 'through colonised lens'. Indigenous traditions shaped our methodology and also helped us create bonds with each other and to understand ourselves. We must address the racist past the development of methodology including oral history and we must develop the potential for indigenous practices to bring a full selves to our research including a process of spiritual recovery necessarily linked to political self recovery. This s only the beginning [Dillard, CB seems to do a lot of work — there are several pieces between 2006 and 2018, all of which mention spirituality and remembering culture] |