| Notes on:

Bernstein, B. (2000) Pedagogy, Symbolic

Control and Identity. Theory, research,

critique. Revised edition.

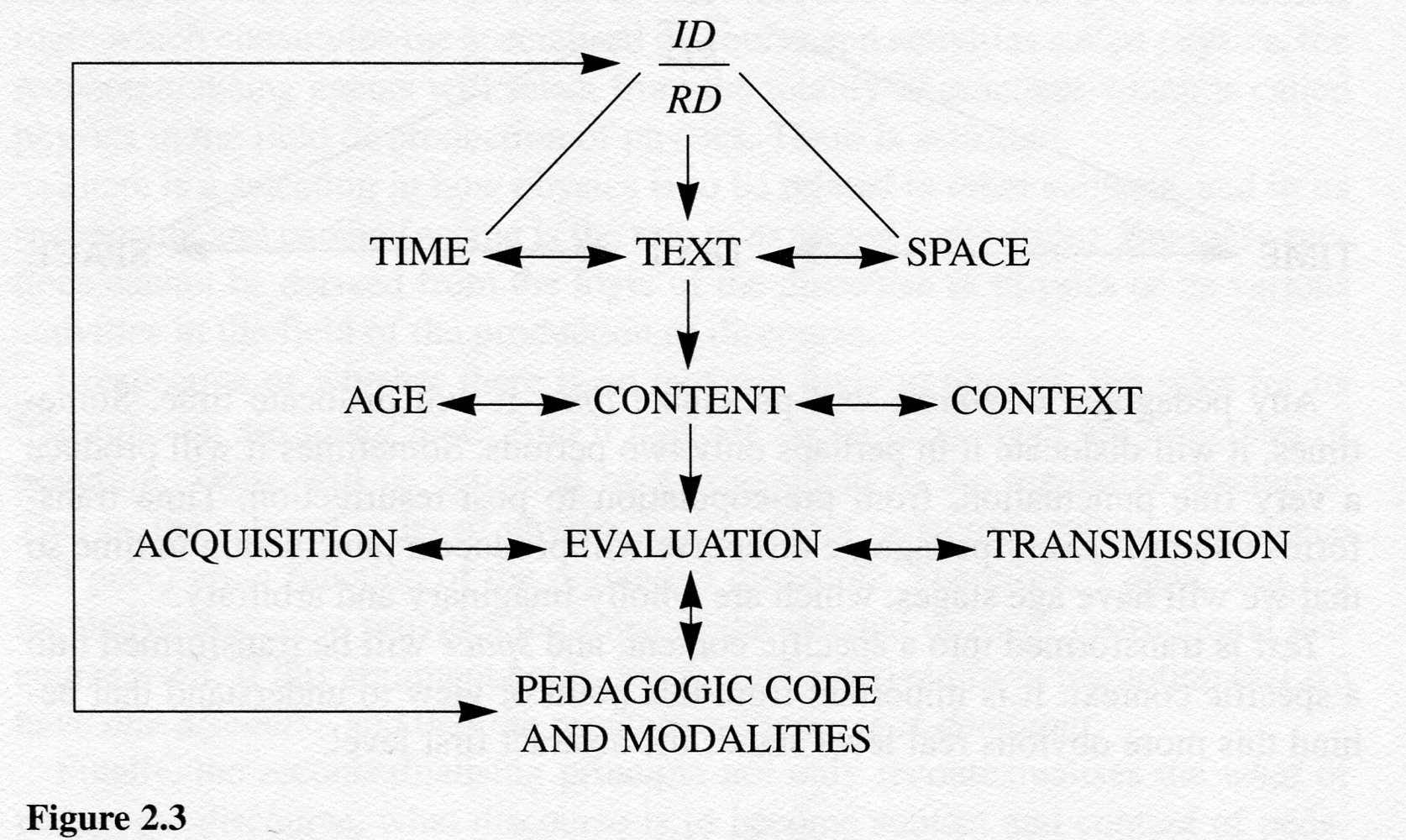

Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. Dave Harris Chapter one Pedagogic Codes and Their Modalities of Practice (3-24) This model is intended to be universal and to include pedagogic practices outside schools, including say relations between architects and planners. This produces a general model that focuses on 'underlying rules shaping the social construction of pedagogic discourse and its various practices', rather than say aspects of contemporary educational systems. This is to stand between more general series [presumably reproductive ones] to explain the relationship between knowledge and consciousness. Reproduction theories are too limited and cannot provide sufficient description of pedagogic agencies and the discourse and practices, because they focus on education as a carrier of external power, while the actual structure which Carries the power is less relevant. However the logic and the structure of pedagogic discourse needs to be examined. There is no need to see education as a pathology or for social class to become dominant in this examination. We're after are 'the inner logic of pedagogic discourse',the rules of construction, circulation, contextualization and change, specifically: How does the dominant distribution of power and control generate and legitimize 'dominating and dominated principles of communication'? How does this distribution of principles 'regulate relations within and between social groups'? How do these principles distribute 'forms of pedagogic consciousness'? (4). Power can be distinguished from control although they are 'embedded in each other' (5) empirically. Power relations produce boundaries between different categories which might be groups discourse or agents. Power produces 'dislocations … punctuations in social space', the relations between categories, the legitimate order between them. Control however 'establishes legitimate forms of communication appropriate to the different categories', within the categories, or socializing individuals and offering a potential for both reproduction and change. Pedagogic discourse features different categories, pedagogic practices different forms of control, and together they offer 'forms of pedagogic communications'. However, a special terminology is required to show how macro relations and micro interactions are related, and this terminology should also operate with general principles, generate specific descriptions, and produce a range of modalities of discourse and practice, including some which do not currently exist. Classification is the concept used to describe the relationship between categories, but it does not refer to some underlying defining attribute [I think it must in practice], but rather refers to relations between categories. These relations need not be discursive ones, but describe, for example 'the division of labour'(6) [hints at some organic unity or solidarity?]. School subjects have their own boundaries and identity, but this is not justified by some external discourse. Categories only exist in relation to others and they can define themselves against others [politically?]. However, we can see these as 'other categories in the set' [so what defines the set?]. We can see the exercise of power in the gap between categories [so more confusion here because it's categories of discourse which apparently maintain 'the principles of their social division of labour']. Barriers can be broken down and categories can lose their identities, so the 'insulation' has to be maintained, or at least its principle does. What preserves insulation is power and power relations [we seem to have come full circle here]. There are strong and weak classifications different degrees of insulation between categories. With strong classification 'each category has its unique identity, its unique voice, its own specialized roles of internal relations'(7) [so it is some kind of ideal or formal possibility?], but classifications 'always carry power relations'[power is something external again]. These power relations are arbitrary, but are 'hidden by the principle of the classification' which comes to take on a reality of its own connected to the integrity and coherence of the individual. All the contradictions and dilemmas have to be suppressed, and this also functions as 'a system of psychic defences', although these are 'rarely wholly effective'. As examples of classifications, we can compare the medieval university with the modern one, as examples of stronger and weakening classifications. [Description of the medieval university follows, with strong internal divisions between mental and manual practice, further reflected in the relationship between the rhetorical and logical trivium and a more applied quadrivium. These feature different languages, roughly linguistic and mathematical. God integrates the two, permitting an excepted order of precedence or 'regulated discourse' to be constructed in the trivium and then later applied. We can also see this as constructing inner consciousness before going on to consider the structure of the outer. This reflected a division inside Christianity itself - so it reflects this division in pedagogy? It also forms the characteristic European notion of consciousness as a relation between inner and outer - the pedagogy does or Christianity does? The church provides the underlying power to maintain strong classifications. In the modern university, European knowledge is restructured, however and singular discourses are grouped together in regions. Apparently, modern subjects can be seen as singular discourses because they have unique names [!] and have 'very few external references other than in terms of themselves'. However, they became regionalised following recontextualization, and this regionalization was based on 'a recontextualizing principle', although we don't seem to be told what it is --doubtless a reworking of one of the descriptions above. However, these movements to different forms of classification provide 'spaces for ideology to play'(9), which is not defined either. New forms of competition for resources and indifference broke out within and between regions. Overall, what an entirely unhelpful example!] Looking at institutions, we can see strong and weak classifications in schools or universities. For example, school departments 'represent discourses', and they can be strongly classified. It is common [later I think this becomes 'essential'] to accompany this with strong classification between the institution and the outside as well. Strong classifications therefore produce a hierarchy of knowledge between common sense and school knowledge [must do, in the interests of formal coherence?] . Staff are also closely identified with departments and this is a symbolic allegiance, 'the sacred reason' (10), although 'the main reason' is that promotion follows from departmental activity. The reproduction of pedagogic discourse itself is not collective, since the staff are weakly related and specialized. 'Thus, the contents are not open to public discussion and challenge' [by teachers, that is]. The diagram (on page 10) also resembles a temple, a symbolic representation 'of the origin of the discourse' in Greek philosophy and the church [all this is based on the way he has drawn the diagram of course]. Discourses are collected in, er, a collection code. In weakly classified schools, boundaries are permeable, but this also makes the institution vulnerable to 'communications from the outside'. Staff must be members of a strong social network to integrate the differences, and their relations 'cohere around knowledge itself' [the whole thing is riddled with idealism]. This also provides an alternative power base against the hierarchy. Strong classifications of discourse also produced temporal dislocations, 'although it is not logically necessary' (11), since strongly classified knowledge empirically produces a progression from local knowledge through the usual steps of simple operations to general principles. If children drop out 'they are likely to be positioned in a factual world tied to simple operations, when knowledge is impermeable. The successful have access to the general principle'. [We only ever learn general principles through acquiring school knowledge -- now enter Rancière]. Some particularly successful people go on to create the discourse itself and realise its fundamental incoherence. The whole discussion shows two rules. First, where there are strong classifications, things must be kept apart [a definitional rule again, a rule stemming from his model], and vice versa. We should go on to ask about whose interest is behind these options [although I don't think he ever does -he leaves us to imply that some dreadful hierarchy is at work] Classifications construct social spaces, as translations of power relations, with the affects of creating social divisions of labour, identities and voices. The arbitrary nature of power relations are disguised by the classifications and various psychic systems of defence when they appear necessary. Pedagogic practice itself and how it forms consciousness requires a notion of control to regulate and legitimise communication. Framing affects such control, in any pedagogic relationship. Framing helps people acquire 'the legitimate message' (12) and also establishes voice, although the two 'can vary independently', since different modalities can establish the same voice, while more than one message can carry the voice [so what else affects voice?]. Framing helps the discourse to be realised, meanings are to be put together and in what forms, people related in a given context. Control was exercised over the selection of the communication, its sequencing and pacing, the criteria and 'the control over the social base' (13). Framing can be strong and weak, although the loss of control to the acquirer in weak framing can be only 'apparent'. Difference strengths of framing can affect the different aspects of control above. There are two systems of rules, those of social order and those of discursive order [rules here are not specific ones as in the above example, but abstract necessities, functional prerequisites]. The first one relates to expectations of acquirers and can be a source of labeling - 'which labels are selected is a function of the framing'[?] [A strange bit here, apparently strong framing seems to be associated with positive labels, but weak framing means more problems for the acquirer]. With discursive order, we are talking about selection, sequence, placing and criteria. Framing can be represented in a little equation, page 13, where instructional discourse appear as above the line and regulated discourse below it, this apparently shows that 'instructional discourse is always embedded in the regulative discourse, and the regulative discourse is the dominant discourse [empirically or logically?] Elements of the discourse can be framed with varying strengths, and so can regulative and instructional discourses. They do not 'always move in a complementary relation to each other. But where there is a weak framing over the instructional discourse, there must be weak framing over the regulative discourse'. In general, if framing is strong, we have a visible pedagogic practice with explicit rules, and where it is weak we have an invisible pedagogic practice [the invisible practice is a bit like the hidden curriculum and pedagogy, where it all goes on implicitly, and the example cited elsewhere is the progressive primary school where the whole set of social relations teaches something]. Now to 'write pedagogic codes'(14) [a pompous way of saying supply more detail]. Classification and framing can be strong or weak and combined producing a range of modalities [well, four, surely?]. Now we find that classification relates both externally and internally, to external relations and also to internal classifications like those 'of dress, of posture, of position', and spaces and objects can also be strongly specialised or classified. The same goes for framing. The external value relates to communications outside that pedagogic practice which affect it [the example is whether or not you pay the doctor, which will affect the sorts of legitimate communication you can have with them. Your identity externally can be strong or weak]. Here, 'social class may play a crucial role', and external dimensions of school framing can 'make it difficult for children of marginalised classes to recognise themselves in the school'. So we have more complications on the four basic possibilities, since classification and framing are not only strong or weak, but internal or external [I still think this only gives 16 possibles]. There is one of Bernstein's nice little equations to show the elaborated orientation on page 15 - it has strong classification and framing [I think. Actually the diagram seems to show all the possibilities again, but in that case the elaborated orientation would be no different from the restricted one in the abstract, but only when we actually entered values]. Classification and framing produce rules of the pedagogic code, 'that is, of its practice, but not of the discourse'. The changing values of classifications and framing produce different organisational practices, discursive practices, transmission practices, psychic defences, concepts of the teacher, concepts of the pupils, concepts of knowledge itself and expected pedagogic consciousness. There is always pressure to weaken framing, because pedagogic practices are always an arena for struggle over symbolic control. Framing is the most likely source of change in the classification. The connection between classification and power never completely removes 'contradictions, cleavages and dilemmas', at social and individual levels. One problem with the notion of cultural reproduction is that these possibilities ['rules' again] are usually never specified. [well --not formally identified in these terms nor seen as 'rules' ? But internal and external change factors are clearly listed in say Homo Academicus] We can suggest some possibilities. If there are changes from strong to weak, either with framing or classification, we can always ask 'which group was responsible for initiating the change?', dominated or dominating. If values are weakening, which one still remains strong? [And how do we answer these questions?] Pedagogic practice therefore has its own internal logic [based on the abstract possible combinations] , and classification and framing produces different modalities, especially of 'official elaborated codes'(16) [so are there unofficial ones?]. These can shape the consciousness of the acquirer, but we need to explore this and go beyond transmission. Such consciousness of acquirer and transmitter can show 'biasing', although we are not going to refer to ideology, because the system constructs ideology. It is 'a way of making relations. It is not a content but a way in which relationships are made and realized'[weird and confusing -- could be that ideology is or is embedded in practices as in Althusser?] A nice new diagram appears on page 16 to put together all the concepts developed and show their [formal] dynamics. These will demonstrate 'the model of acquisition within any pedagogic context'. First there is a connection between classification and 'recognition rules... at the level of the acquirer' (17). As classification strength changes, so individuals are able to 'recognise the speciality of the context that they are in'[strong classifications mean you're in a special educational situation]. Classification shows that one context differs from another, and some contexts are distinct and require a particular orientation for communication. In university seminars, the members 'share a common recognition rule' whatever their disciplinary background, and this helps them read the context and contribute appropriately. It's not always easy for him to infer a discursive context for the particular questions, however, and in this case the weakly classified context can create ambiguity [so is this saying that students do recognise what's going on better than lecturers do? Or that seminars can be both recognized and not very well recognized? Or that recognition affects behaviour, but lack of recognition affects content?]. Apparently, strong classification produces strong recognition rules and power relations and this helps to produce legitimate communication. Some children from the marginal classes might not realise this and remain silent in school. This shows the key effects of power in distributing recognition rules. However, even if we recognise that the context is specific, we still might find it difficult to produce legitimate communication, and again children of the marginal classes find themselves in this position: 'they may not possess the realization rule'. As a result, 'they will not have acquired the legitimate pedagogic code, but they will have acquired their place in the classificatory system'. This is the main experience of school for them. Recognition rules enable appropriate realizations, but realization rules are required to actually put meanings together and make them public, producing legitimate text. This can be affected by the different values of framing. We therefore have an explanation of classification as a result of power, and framing values as the result of control [rather as translations of them, selecting and distributing recognition and realization rules]. However, pedagogic practice 'is essentially' interactive, defined by classification and framing procedures. The acquirer is expected to construct legitimate text, which may cover only 'how one sits or how one moves', since 'the text is anything which attracts evaluation' (18). Evaluation itself is a condensed version of the pedagogic code, its classification and framing procedures, and the relationships of power and control that have produce them. However, texts can change interactional practices, that is change classification and framing values [no examples?].[So texts must have or be a power of their own?] Some research can illustrate the relevance of all this, including some done by Holland [already discussed here]. Here the interest is in how context and tasks produce different readings, including tacit ones. Here the exercise turned on classifying food items as a kind of general issue. Pictures were sorted differently by samples of working class and middle class children. Formally, the task can be described as weakly classified and framed, since children were told to choose any picture and classify them in any way they liked. They gave two types of reason, one referring to the life context [something they had for breakfast for example], and one relying on more abstract classifications [they are vegetables]. This is not just a difference between abstract and concrete thinking because we would then 'lose sight of the social basis of that difference' (19) [what a classic way to put it - we can't accept one term because we want to see social class differences]. We can trace these classifications in terms of direct relations or indirect relations 'to a specific material base', the local context and local experience. Initially middle class children offered indirect reasons, but when all the children were asked to sort the cards again, they were able to switch back to a direct relation to local experience, although working class kids were not. So it looks like middle class kids have two principles of classification, 'which stood in a hierarchical relation to each other'- why did middle class kids choose the indirect form first? Apparently it depends on how you read the coding instructions. Middle class kids realized that in that particular context, classifications were still expected to be strong between school knowledge and common sense knowledge. They had a better understanding of the recognition rule that said there was a strong classification between home and school, 'itself based on the dominance of the official pedagogic practice' (20). This gave middle class kids more relative power and privilege. In another example, secondary schools responded differently to the 1988 Educational Reform Act and the introduction of cross curricular themes. These have arisen as a result of criticism of the narrow subject based curriculum. Students talked about these themes differently, however, some in terms of subject conventions and others in terms of topic orientations and concrete examples. Again there were social class differences [but were they significant? The totals actually look quite close]. Bernstein says it's not clear how this happened, but he says there is a school effect, and one school in particular taught themes in subject-based ways. There can also be an interaction with social class. In any event, strong classification and framing defeats the ostensible purpose of cross curricular themes. Weakening a classification between school knowledge and every day knowledge 'could lead to a perception on the part of the student that themes were not really official pedagogic discourse, as the researchers found' (21). [Actually the extract isn't terribly clear in my view, but Bernstein says it shows that some students are aware of subject based recognition and realization rules - Rancière would have a field day with this!]. These examples show the 'empirical relevance' of the models, which show how power and control 'translate into pedagogic codes and their modalities'. (22). Bernstein also thinks he has 'shown how these codes are acquired and so shape consciousness'[ridiculously ambitious]. He has linked macro structures of power and micro processes of the formation of pedagogic consciousness. The models reveal order and change, but above all they 'make possible specific descriptions of the pedagogising process and their outcomes'[well he has generated number of possibilities by combining structure and options]. Now we need to look at the construction of pedagogic discourse. Appendix. The model has been criticised because it doesn't adequately describe organisational or administrative dimensions. The organisation can be seen as the container for something that is transmitted, and thus offers 'the primary condition without which no transmission can be stable and reproduced' (23). There is a necessary level of administration of staff and resources and the management of external responsibilities. The relation between these and the transmitting agents affect the shape of the container. Changes in classification and framing can affect the government of educational institutions and therefore affect the shape of the container, and pedagogic codes can be relatively stable or unstable, producing different levels of conflict and consensus. This in turn will require different levels of management. However the management of resources itself, the 'economy of the container', is not always related to the code modality, and can deal with different code modalities. There are other effects independent of code modality, extrinsic to them. These can be seen as 'external biases imposed by some power (e.g. State)'(24). This complicates the picture and the metaphor of the container and the contained, since 'bias operates at a different level as it mediates between some external power and the internal regulation of the agency'. We therefore need to identify the parameters involved - 'bias, shape, stability, economy' and develop a new concept to include them. To some extent, we can use the old notions of distributive rules to cover resources as well as discourses. We can extend the notion of regulative discourse to include management functions and even external biases. However, we need a concept that shows how it can regulate pedagogic code while also being dependent on it [!], to show how the fundamental 'mode of being of the agency' is regulated. The notion of 'pedagogic culture' will do this, reflecting the way in which agencies cope with bias, shape, stability and economy. [So nothing falsifies or tests the model - we just generate endless ad hoc hypotheses to incorporate criticism] Chapter 2. The Pedagogic Device We want the general principles that govern the transformation of knowledge into pedagogic communication, whatever the knowledge might be [in other words very general abstract principles again, and not actual effective rules in empirical circumstances]. This could be unnecessary because we have some empirical understandings, but these are often see pedagogic communication as a mere carrier for external power relations or ideology, or for skills and legitimate identities. If we are to study what is actually carried or relayed we have to examine 'social grammar, without which no message is possible' (25). The language device has several formulations, but basically it examines how roles are acquired and how interaction is regulated. For Chomsky, this device is independent of culture, existing 'at the level of the social but not at the level of the cultural' (26). It has just evolved and 'we could not leave a device as critical as this to the vagueness and vicissitudes of culture'. [The diagrams are very limited, with meaning potential at one end and communication at the other, with black boxes called language device and pedagogic device respectively in the middle. There is also a feedback loop which acts 'either in a restricted or in an enhancing fashion'. Since rules vary with the context, there are contextual rules to understand local communications [!]. They are relatively stable over time but contextually regulated. One question which arises is whether this affects the apparent neutrality of the language device, [whether there are some emergent effects]. Halliday has argued that these roles are not 'ideologically free, but that the rules reflect emphases on the meaning potential created by dominant groups' (27). Perhaps it is these dominant interests that produce the relative stability of the rules. [As well] language and speech are dialectically interrelated. This is a complex argument and there are contradictory views about it. At one level the language device clearly has some built in classifications, especially gender classifications, and gender equality suffers from having to work with these in built classifications [the example is the term 'mastery'] [gender is never mentioned again from what I can see]. So both the carrier and the carried have contextual rules and neither 'is ideologically free'. Turning to the pedagogic device, we can also identify the internal rules that regulate pedagogic communication which 'acts selectively on the meaning potential', the latter referring to all discourse that can be pedagogised. The pedagogic device continuously restricts or enhances realizations of potential pedagogic meaning. The formal structure is similar to the linguistic device [because he has drawn it this way]. There are rules to regulate realization and these rules are intrinsic and relatively stable, although they 'are not ideologically free' (28). They are 'implicated in the distribution of', and constrain forms of consciousness. Both language device and pedagogic device are sites for conflict and control, but only the pedagogic device can produce an outcome 'which can subvert the fundamental rules of the device'[surely not so, we can produce challenging avant-garde linguistic utterances as well. This is Bernstein's implicit functionalism again?]. The pedagogic device provides the 'intrinsic grammar of pedagogic discourse' where grammar is used 'in a metaphoric sense' [clear as forking mud]. This grammar is realized through distributive rules, recontextualizing rules, and evaluative rules. [I am still trying to figure out what I find difficult about this notion of a rule rather than a convention or a constraint - is it that rule implies some structural, consensual, functional operation?]. These rules are related and they also feature power relationships between them [a continuing ambiguity about power as well]. Distributive rules particularly regulate relations 'between power, social groups, forms of consciousness and practice'; recontextualizing rules 'regulate the formation of specific pedagogic discourse'; evaluative rules 'constitute any pedagogic practice', since the purpose of pedagogic practice is to 'transmit criteria', and this provides 'a ruler for consciousness'[compare this with dispositions in Bourdieu, which are socially sedimented, unconscious, and embodied]. [This argument means instructional and regulative discourse are also organized in a hierachy as we shall see -- separate arguments are really the same argument. This is an axiomatic system] There are two different classes of knowledge that 'are necessarily available in all societies' and are 'intrinsic to language itself' - the thinkable and the unthinkable. This provides two classes of knowledge, the esoteric and the mundane, or the 'knowledge of the other' and 'the otherness of knowledge' [all of them variants of the sacred and profane?]. There is also the knowledge of the possible and the possibility of the impossible. The line dividing these two classes varies historically and culturally. If we compare small scale non literate societies with more complex ones, religion regulates the division between the thinkable and the unthinkable, but in 'a very brutal simplification' (29), it is the 'upper reaches of the educational system' these do not always originate divisions, but they control and manage them. The mere thinkable is still within schools. However simple and complex societies have a similar order of meaning [a key functionalist assumption again]. It would be wrong to see it as an abstract vs. concrete division, since 'all meanings are abstract'. However, the abstraction takes different forms. In all cases it 'postulates and relates two worlds', the material and the immaterial, the mundane and the transcendental. What this means is that meanings have different relations to the 'specific material base', a direct one where meanings are 'wholly consumed by the context' (30), and an indirect one, which both create new meanings and unite the two worlds. This division is reflected in a division of labour and a set of social relationships [and not the other way about]. Indirect meanings produce a 'potential discursive gap', but this is not a dislocation. Instead, it offers alternative possibilities and realizations, offering a space for the unthinkable and impossible, something yet to be thought, and this is both 'beneficial and dangerous at the same time'. Any distribution of power tries to regulate the realization of this potential, since it must be regulated [for social order, but particular groups are also able to follow their own interests in preventing alternatives]. The religious systems of simple societies are a good example. The 'paradox' of the gap [between beneficial than harmful outcomes, I assume] is covered by distributive rules which govern those who can access the site. [Another?] paradox arises because the device itself cannot do this effectively, and contradictions are 'rarely totally suppressed', and the pedagogic process itself reveals the possibility of the gap and makes power relations visible. There is a connection with the notion of field, which is constituted by distributive rules, which are 'controlled more and more today by the state itself'(31). Recontextualizing rules govern what counts as adequate pedagogic discourse, specialized communications. Pedagogic discourse itself is 'the rule which embeds two discourses', relating to skills of various kinds and to social order, instructional and regulative discourse. Bernstein thinks that instructional discourses are always embedded in regulative discourse which is the dominant one [repetition of what he said above]. Pedagogic discourse combines the two, so it is wrong to separate the transmission of skills and the transmissions of values - 'the secret voice of this device is to disguise the fact that there is only one' discourse (32). [Is this ideology as well? Or maybe a latent function?] Pedagogic discourse appears as neutral compared to the familiar subject based discourses. So we need to redefine it as a principle not a discourse [why not say that originally, dick], regulating the connection between the other discourses. However, it does give rise to a specialised discourse of its own [!]. It also creates a gap between discourses and the pedagogised sites or forms, and again we have 'a space in which ideology can play. No discourse ever moves without ideology at play'[ideology here means the disguised interests of powerful groups? Or just 'worldview'?] This move also turns it into 'an imaginary discourse', a mediated or virtual one. It also produces 'imaginary subjects' (33) [a note on this distinction between the real and the imaginary says it is supposed to draw attention to an activity unmediated by anything other than itself, compared to one when mediation is intrinsic in practice. The example is between carpentry and its pedagogic equivalent, 'woodwork'. Real discourses are related to the social base again. Presumably, then they are also restricted in what can be thought - practice itself can never produce new possibilities for thinking? All manual occupations seem to produce some kind of mechanical solidarity]. We can put this in formal terms - 'pedagogic discourse is a recontextualizing principle', selecting, and organising other discourses, but never identified with them. This is 'a recontextualizing discourse', and it creates 'recontextualizing fields' with suitable agents 'with practicing ideologies'[ideology here appears to be world view?]. Recontextualization creates 'the fundamental autonomy of education'. There is even an 'official recontextualizing field' operated by the state, and a 'pedagogic recontextualizing field' inhabited by specialist educators, and this provides the relative autonomy and struggle [none within the state? No regulation of the specialist educators by the state - he admits that today the state is attempting to weaken the PRF]. Since moral discourse creates the criteria for subsequent instructional discourse, we can see that in general regulative discourses affect the order in instructional discourses. [repetition again really, going from a specific case to some underlying principle or rule]. We can see this with physics. We distinguish between physics as the production of the discourse, and physics as a pedagogic discourse: the former displays variety, but the latter is controlled by devices such as textbooks, written by pedagogues and only 'rarely physicists'. As a result, there is no formal logical link between the discourses, since pedagogues select. The selection also depends on how physics is to be related to the other subjects, how is to be sequenced and paced, and these 'cannot be derived from the logic of the discourse of physics or its various activities'[so this is almost the opposite of the 'powerful knowledge' merchants' argument that school curriculum, at least, should reflect the vertical hierarchical structures of proper sciences? Or perhaps they are just saying we should design the curriculum and let pedagogues figure out how to teach it?]. The rules for the transmission of physics have a reality of their own - they are 'social facts' (34), inevitably incorporating selection [weird]. [Somehow] the overall regulative functions of the discourse provide the rules of the internal order of instructional discourse - it is dominant [I think this is just saying that pedagogues have to work with objects that are already selected as being important, as social facts. Whether Bernstein means this in the full Durkheim sense is not clear - it still seems to imply some consensus or some powerful imposition of a consensus. Hasn't the discourse of physics itself done much to undermine this? And is almost a way of saying that the objects in pedagogy are indeed arbitrary?]. Recontextualizing principles also produce a theory of instruction. This is never 'entirely instrumental' since it also imports from the regulative discourse models of learners and teachers and their relation. Pedagogic discourse has to be transformed into pedagogic practice. This involves a specialist notion of time, a text and a space and their interrelationship. This takes the form of 'very fundamental category relations' and again these have 'implications for the deepest cultural level' (35) [all this follows as another implication from the connection between pedagogic discourse and regulative discourse, between pedagogic order and social order in general]. Pedagogic discourses can operate at a very fine level, producing, for example the notion of age stages to punctuate time, although these are 'wholly imaginary and arbitrary' (35). Both text and spaces are also organized into a specific context, but again behind the specifics stand more abstract levels. Beneath lies another level, that of actual pedagogic practice and pedagogic communication, which features acquisition, evaluation, and transmission, where the 'key to pedagogic practice is continuous evaluation'(36). The pedagogic device condenses these levels, providing an overall 'symbolic ruler for consciousness' [consciousness is assumed to follow from pedagogic practice]. It is a form of religious practice with its descending levels to control the unthinkable. [Gives the Durkheimian game away. The wonderful diagram on page 36 indicates the full story, where ID is instructional discourse, RD is regulative discourse, and dividing them by a horizontal line does not indicate division, but embeddedness.  Why practice should be an indicator of a pedagogic code with its modalities is still a puzzle - why use the term code at all unless you wish to imply some structural determination? Note that codes relating to the (un)thinkable do not appear where they should in the diagram below -- on the left even before social groups. There seem to be no feedback loops now either]. We can see homologies between religion and education. We can follow Max Weber here as well, with his division between prophets priests and laity being homologous to producers, reproducers and acquirers. There is a 'rule' that people can only occupy one category at a time, and that while prophets and priests are in opposition, priests and the laity are in relations of 'natural affinity' [Bernstein is only implying that these social relations affects the pedagogic field too - I would have said there is opposition between all three categories]. We now have an even better a model of the pedagogic device on page 37 showing the connections between social groups and various rules and fields and processes.  This is how consciousness is regulated [this is actually only assumed to follow from processes, although it is already smuggled in with evaluation rules], and cultural transmitted. However there is no determinism and there are sources of indeterminacy: Internally the device controls the unthinkable, but in the very process of doing so 'makes the possibility of the unthinkable available' [deviance is the same as the principle of conformity in Durkheim's terms] (38). Externally the distribution of power outside itself has potential challenges and oppositions, and the device shows this background struggle: it 'creates an arena or of struggle for those who are to appropriate it'. Overall, the claim is that Bernstein has exposed 'the intrinsic grammar of the device' and its 'hidden voice'. As it processes, it regulates. Its ' [very] grammar... codes order and position' while at the same time containing a potential for transformation. Another note discusses the French System where university staff circulates to the lycée as a rare exception to the strong classification between those who produce discourse and those who recontextualize it. However, recontextualizers rarely go the other way, and this might be preserved by increasing distinctions between research only and teaching only institutions in the UK. Another note points out that the texts produced by pedagogy are also imaginary. Unlike the texts of producers, they are not expected to be original and unique. Pedagogic texts instead offer 'intra-textuality [in the] process of constructing unique authorship'. [Overall, I'm not surprise that this article has been so controversial, and so tidied up in commentaries. Apart from the massive assumptions, principally about consciousness and about the effects of social context in limiting what can be thought, there is a clear functional argument throughout. By and large, power is necessary for order, even though it occasionally has to be adjusted through functional conflicts. This is also an interesting text for people like Maton who want to accuse Bourdieu of operating only with the arbitrary - it is hard to tell because Bernstein uses ideology in different terms, but it looks as if there is an arbitrary social order behind all these developments as well, at least once the basic paramters have been established. The non-arbitrary in Bernstein only amounts to social facts like the split between the sacred and the profane. Certainly, pedagogy is arbitrary compared to the operation of real discourses. I suppose that by calling them real discourses, you might think that Bernstein is some kind of social realist, but he insists that that only means that they are closely connected to their material bases: this is a theory of verisimilitude at best]. Chapter 3 Pedagogising Knowledge: studies in recontextualizing [At last! Some concrete detail. This is a very good discussion of the neolibleral turn, but with only an implicit marxism. All the terms introduced in the above are just used descriptively] Titles [that is academic classifications] relate more to positions in intellectual fields than to the content of actual arguments, so this one could have been called anything with functionalist, Althusserian, Foucaldian or postmodern resonances [strikes me as both defensive and arrogant]. In the 1960s, there was a notable shift towards the notion of agent or member competence in a number of different intellectual fields, and this had consequences for pedagogy. We're not going to discuss the origin of the convergence [shame, because it doesn't seem to have been predicted in the earlier work]. Competences 'are intrinsically creative and tacitly acquired in informal interactions. They are practical accomplishments' (42), somehow they escape power relations, and agents can now negotiate social order and interact with various kinds of cognitive and linguistic structures. They are assumed to be culture free. They 'embrace populism'. There is an implicit logic that says that all people are inherently competent and that there are common procedures with no deficits; the subject is active and creative; the subject is self regulating and this is benign; this brings skepticism towards hierarchy and emancipation; there is a focus on the present tense as the most relevant time. These characteristics can apply unevenly but most of them are present. It is an 'idealism of competence, a celebration of what we are' (43), but it involves an abstract individual somehow outside power and control. The idea clearly resonates with the liberal progressive and radical ideologies of the 1960s and was taken up by those in education, even though most of those formulating their theory were not really concerned with education. The position also entered conflicts in the intellectual field, and were crucial in taking on various opposing positions, including 'Piaget on behaviourism, Garfinkel and structural functionalism'. Structuralism even in Levi Strauss was one strand, but there was also ethnomethodology and other strands in sociolinguistics. There was a common anti positivism. Somehow, these arguments became important to the theory and practice of education, including members of the official recontextualizing field, as in the Plowden Report, as well as among the expert pedagogues 'an unusual convergence'. At the same time, different inflections applied more to different educational disciplines - Piaget to educational psychology, for example. This led to a specific pedagogic practice especially in primary and preschools areas, constituting 'a competence model' and struggling with its opposite 'the performance model', based on specific outputs particular texts and specialized skills. [A diagram on page 45 tries to refer back to classification as well, especially with the main issues of space time and discourse]. In more detail: At the level of discourse, competence models favour 'projects, themes, ranges of experience, a group base', acquirer control, celebration of difference rather than stratification, weak classification. Performance models offer specialised subjects, 'skills, procedures which are clearly marked with respect of form and function'. Acquirers have less control and their texts are graded and ranked. There is strong classification. In terms of space, competence models do not distinguish specially defined pedagogic spaces and allow acquirers to construct different spaces and to circulate between them. Classification is weak. In performance models there are clear boundaries and markings and regulations, with strong classification. In terms of time, competence model see the present tense as the major mode. Time is not particularly punctuated or marked, nor is the future particularly emphasized. Weak pacing also features. Only the teacher can know what each acquirer is revealing a particular moment, and uses this as the basis for provision. When it comes to evaluation, competence models again emphasise what is present in the product, using diffuse and implicit criteria of evaluation. However, there is more emphasis on regulated discourse criteria of conduct and manner. In performance models the emphasis is upon what is missing in the product, referring to explicit and specific criteria for legitimate text. For control, children do not have their experience structured by space, time or discourses and positional control is a low priority. Control is likely to 'inhere in personalised forms', hence forms of communication 'which focus upon the intentions, dispositions, relations and reflexivity of the acquirer' (47). This is the most favoured mode. In performance models, space time and discourse do structure and classifying and therefore 'constitute and relay order'. Instructional discourse disciplines. A more economical form of control appears, not personalised. Neither of these techniques work smoothly necessarily, and acquirer subversions are 'mode specific'. Pedagogic text in competence models is not seen as a product of the acquirer, but rather something that reveals their development and can be diagnosed by the professional teacher, drawing on suitable 'social and psychological sciences which legitimise this pedagogic mode' (46-7). It follows that these meanings are available only to professionals. In performance modes, the focus is on the text itself as the performance of the acquirer, and professional teachers offer explicit pedagogy ease and professional grading. The emphasis is on both past and future. But the pedagogic practice itself constructs the past for the acquirer. Notions of autonomy vary, competence models assume a wide range of autonomy, although teacher autonomy is often compromised because they all have to practice the same pedagogy. There are also context dependent elements which require local autonomy. There is no reliance on outside pedagogic resources like textbooks. There is less availability for public scrutiny and accountability, especially as outputs are difficult to evaluate. There is no strong tie to predetermined futures either [so no coaching for grammar school or university]. There are different performance modalities, some relate to the future, 'introverted modalities' and some relate more to external regulation, 'extroverted modalities'. The first looks like the exploration of the specialised discourse itself is autonomous, whereas the second one relates to something external like the economy or the job market. At the same time, even introverted modalities are subordinate to external curriculum. There can be individual variation at the level of teaching practice aimed at increasing performance, although external criteria limit this autonomy. The need to market institutions can also produce a certain kind of autonomy [well, market variation at least]. There is an economic factor. The costs of competence models are higher, and so are the cost of training teachers in the 'theoretical basis of competency models' (49) [selecting people for teacher training is also 'likely to be stricter' because the qualities required are 'restricted and tacit']. There is a substantial cost in terms of time and the construction of pedagogic resources, and in evaluating each acquirer. Parents have to be socialised, extensive feedback is required on development, teachers have to interact a lot in order to plan and monitor. Usually, it is the individual, committed teacher who bears these costs, and this can lead to 'ineffective pedagogic practice' due to teacher fatigue. Transmission costs of performance models are relatively lower for all those reasons. Accountability can also be managed more objectively. Performance can sometimes be routinized [these days, put online]. It is easier to regulate the costs and to impose other controls. A different kind of commitment and motivation is required. We can spell out the differences in more detail. Competence models stress the similarities between people which are seen as complementary. However, this splits into three different options. The first one, 'liberal/progressive' is located within the individual and to things that all individual share. It intended to emancipate the new notion of the child away from the old repressive forms of authority, based on a 'new science of child development'(50). The caring ethos opened professional careers for women and attacked patriarchy. Individual potential was to be released. Advocates and sponsors included the new middle class 'in the field of symbolic control'[referring to empirical examples of these correspondences? - in class codes and control vol. 3]. The second model looks at similarities within a local culture and it is that local culture which is usually dominated, but which has hidden communicative competences. This is the populist mode. The third mode agrees that competence is found in local dominated groups or classes, but focuses on various material and symbolic opportunities to overcome domination and achieve emancipation. This is the radical mode, associated with Freire, and 'often found in adult informal education' (51) Although these competence models share a focus on similarities, they are often found opposed within the pedagogic recontextualizing field. They all feature an invisible pedagogy. The radical mode is not found at all in the official recontextualizing field, and only appears in the PRF if there is sufficient autonomy. Performance models also differ according to how their texts are specialized. They emphasize '"different from" relations'. They are 'empirically normal across all levels of official education', so that competence models can be seen as resistance or interruptions. The variables for performance models include whether they are singular or regional, with the former offering much stronger boundaries and hierarchies in the intellectual field its practices, its examination and its licences. Regions follow where singulars are recontextualized into larger units [some examples are given, but not the principle, apparently much depends on the social base]. They threaten the culture of singulars and include 'journalism, dance, sport, tourism' (52). Modular forms also help. Regionalization opens the structure to greater central control, but they must also remain autonomous in terms of content so they can be more responsive to markets. The classification of discourses is weakened, and so is subject identity, which becomes 'projected' rather than 'introjected'. These trends are less obvious in schools, and cross curricular themes have been resisted. There is also a generic performance mode, operating outside pedagogic recontextualizing fields, as in the innovations introduced by the Manpower Services Commission or the Training Agency. These became 'the distinctive "competences" methodology', as in NVQs. They focus on work and life outside school. They are located primarily in further education, and this transformed the professional culture of FE and weakened 'both the liberal education and technical craft tradition'. They also feature misrecognition, seeming to be based on a functional analysis yielding specific competencies, thus borrowing from the competence model. In the process, they have rejected any notion of a cultural basis for stills tasks practices and areas of work and have produced 'a jejune concept of trainability'[so who misrecognises here? Does he thinks that teachers and students are taken in by this sort of hijack? Why is this a misrecognised version and not just a hybrid version? Another option is offered below in terms of a shift back from competence to performance mode]. All this tells us something about the potential of the recontextualizing field in the contemporary context [rendered as 'I am now in a position to construct the discursive potential of the recontextualizing field which characterises the contemporary context', 53]. These examples show the increased importance of 'the dominant ideology in the ORF', and the elements of relative autonomy in the PRF. They reveal oppositions within recontextualizing fields. There are however shared preoccupations - competency models stress development of consciousness, are therapeutic, and 'are directly linked to symbolic control' [that is emphasize the symbolic and cultural] (54), while performance modes are more directly linked to the economy. The emergence of a range of singulars arises from the division of discursive labour, and that in turn is tied to English nationalism and imperialism, including the development of economics and social sciences, 'linked to the new technologies of the market and the management of subjectivities' [not much evidence here]. Classics was linked to entry to the administrative levels of the civil service, science is linked to material technologies. This is the 'profane face' of the development of subjects, compared to its 'sacred face' which claims otherness and dedicated identities, the notion of a calling. Singulars create strong boundaries and introjected 'narcissistic' identities (55). Regions also face both ways, linking with the professions outside as well as addressing the need to group singulars. They are likely to become the modal form. [Compare this with the desperate struggles for status inside and outside the official university hierarchy in Bourdieu, where addressing the cultural industries became a strategy for marginalised academics]. New regions particularly face outwards and therefore have to relate to the requirements of external practices, providing a projected identity. Those practices will affect this identity: it is a volatile context. Generic performance is complex. It features 'similar to' relations like competence modes, but finds this in terms of general skills, linked to the market and flexible performance, providing projected identities again. We can classify them [diagram page 56] in terms of the sorts of control and discourse they feature. Control refers to therapeutic or economic functions, and discourse to pedagogic modes [liberal, radical, populist]; specialist performance produces different possibilities for identity and control, and the context outside can act in different ways even on apparently autonomous modes, from external determination, to pragmatic embrace. These tensions can sometimes be managed by classifying strongly introjected and projected elements [especially with modular schemes, theoretical and practical modules] [Bernstein again uses terms like dependency being 'masked', or the need to interpret exigencies]. The modes can be mixed as well, including a case where 'the therapeutic mode may be inserted in an economic mode, retaining its original name and resonances, while giving rise to an opposing practice'[which seems to cover all the possibilities]. The state can embrace particular modes, as with Plowden. Competency modes became dominant in the late 1960s. The obvious resonance with emancipatory ideologies is not the sole explanation. The main factor turns on relative autonomy for the PRF at the time, especially in terms of training teachers. The government changed the particular form of schools, moving towards comprehensives, for example but 'pedagogic discourse was not the subject of legislation' (57). However, 'an autonomous local space for the construction of curriculum' was created. The abolition of selection removed one crucial external regulator, since selective grammar schools had upheld performance modes, usually in terms of collections of singulars. The focus was on something that the acquirer did not already possess, with an emphasis upon the text to be acquired. Learning was considered in terms of behaviourism and atomism. As school organisation turned to a weaker form of classification, a space was opened up and it was not subject to state regulation. At both primary and secondary levels the competence mode emerged and was legitimised by trends in the pedagogic field. Performance modes were attacked as being based on the concept of deficit. Therapeutic emphases focused on empowerment in different ways, individual, cultural and political, and these were in opposition. These discourses are filled the gap and some were embraced by the ORF. As the population bulge appeared, colleges of education expanded and were subject to fewer controls, including over selection. At the same time, theoretical discourses were becoming more specialized. At school level teacher shortages reduced the selective power of management. Full employment put the emphasis on social relations like multiculturalism and leisure, together, these produced new agendas. At one stage, there was even 'ideological rapport'between the pedagogic field and the ORF [plowden] In the 1970s, the state moved to intervene, largely through centralised monitoring and funding, and this 'changed the culture of educational institutions', from the increasing management to more explicit criteria for staff appointments. The role of the market increased and schools were seen to be adding value. Local authorities were stripped of responsibilities. Overall, the PRF lost autonomy, and new discourses were introduced to teacher training, including 'management, assessment' (58). There is also more school based training. Overall, there was a shift to performance models by the ORF, imposed more rigorously, although this varied in different levels of education. Generic modes came to the fore based on a particularly short term conception of work and life, reflecting the need to be flexible and trainable over a lifetime. Everyone now needs to acquire the ability to be taught and to respond effectively, with 'concurrent, subsequent, intermittent pedagogics' (59), producing 'a pedagogized future'. Actors have to find their own meanings from their past and future, and therefore require a specialised identity as 'the dynamic interface between individual career is and the social or collective basis'. This is not just a matter of individual psychology or ambition, but the product of a particular social order offering other identities 'of reciprocal recognition, supports, mutual legitimization, and finally through a negotiated collective purpose'. Trainability is 'empty'. The identity is supported in consumption, and we can see the products of the market as 'signifiers whereby temporary stabilities, orientations, relations and evaluations are constructed'. This generic mode is extended from its base in manual practices to other areas of work. The main pedagogic objective is to produce trainability. This involves the production and reproduction of 'imaginary concepts of work and life which abstract such experiences from the power relations of their lived conditions and negates the possibilities of understanding and criticism'[could be Bourdieu again]. The practice seems to be driven by an increased official control, even in higher education, where it works indirectly, through funding and through research, and in some cases 'industrial niche' (60). This stratified institutions. Intellectual development can involve acquiring academic stars, and this has been a brake on regionalism. Those lower down have been forced to market their pedagogic discourse, and develop projected identities. Regionalization is increased here. Thus practices have affected staff student and institutional identity, and increased diversity and stratification. The move to modularization has assisted this. This offers a difference with performance modes in primary and secondary levels. The national curriculum has clearly introduced stronger classification based on a collection of singulars, and there is increased stake monitoring. However, framing has weakened with the importance of coursework assessment. Somehow 'schools may well exploit such weaker framing over evaluation as a means of increasing their performance' (61) [teach to the test?]. Curriculum monitoring is more central, but schools now have greater autonomy over the budget and administration. Management focuses on performance, whatever the pedagogic discourse, and managerialism has affected all educational institutions, including a greater regulation of selection and promotion. The big dislocation these days is between the culture of pedagogy and management culture, producing a certain 'retrospective' element of pedagogic culture and a prospective one for management. The state seems to have embedded both, and the result might well be 'a state promoted instrumentality', despite the implicit claims for the intrinsic value of knowledge in the school curriculum. However, there are other influences. One note says that the research selectivity exercise is altering the type of research and publication, away from long-term basic research to short term applied research 'with low risks and rapid publication' (63), and this will have effects on both the orientation of teaching and the knowledge base of the students. It has produced a new culture, 'reproduced by new actors with new motivations' . Chapter 4 Official Knowledge and pedagogic Identities: the politics of recontextualization [More detail about identities, using the same sort of framework as above. Bernstein introduces this one as but a mere sketch, but tells us he is a hero who likes to live dangerously]. Official knowledge reveals different biases and focuses with the intention of constructing in teachers and students a particular disposition embedded in particular performances and practices. Abstract analysis produces four possible positions. Pedagogic identity follows from 'embedding a career in a collective base'(66) and a career can have knowledge, moral and locational dimensions. The collective basis refers to the social order in schools as institutionalised by the state. Major changes in bases and careers have occurred, and these are 'international, national, domestic, economic, educational or leisure' contexts, and curriculum reform follows as a response to these changes. Four different approaches to manage change are possible, and these take the form of pedagogic identities. There is a struggle to institutionalise them. Two identities are generated by state resources, and two from local resources, where institutions have relative autonomy (centred and decentred). The diagram on 67 shows the four possibilities. Identities may be restricted/retrospective, or selected/prospective at the state level, and differentiated/decentred (market) or integrated/decentred (therapeutic) at the local level. These different positions may both oppose and collaborate with each other, and there is a struggle to legitimate some and exclude others. The restricted/retrospective identity is a conservative one, insulated from economic change, with the control exercised over 'discursive inputs', or contents, and not outputs. They are 'formed by' hierarchical strongly bounded and sequenced discourses and practices, and they refer to a collective social based in the past, as recovered by some grand narrative. This past has to be stabilised and preserved in the future. This becomes urgent in times of particular secular change, for example in the Middle East or the Russian federation. Selected/prospective identities also refer to the past, but not the same one. It has a more positive stance towards a dealing with change, and it does this by selecting elements of the past and linking it to economic performance. Thatcherism is a good example, with its emphasis on Victorian values and individual enterprise. This time, individual careers are foregrounded. Exchange value dominates the judgement of performance, and this requires control over both inputs' to education and outputs. New Labour also launched a new prospective identity in comparison to the old retrospective one of old labour, stressing preserving communities with participating in the economic sphere. The local decentred identities depend on institutional autonomy. This autonomy are either leads to some therapeutic outcome, or a new flexibility in terms of the market. In both cases, the emphasis is on the present, although these are different presents. In the therapeutic identity, the main stress is on 'personal, cognitive and social development, often labelled progressive'(68). It features 'a control invisible to the student', and stresses autonomous flexible thinking and social relations in teamwork. It is costly. It is currently weak on the national scene, and its sponsoring social group has little power. The identity it offers participants opposes specialisation and stratification, offers weak boundaries, soft management, power 'disguised by communication networks and interpersonal relations'(70), and ideally, 'stable, integrated identities with adaptable cooperative practices'. The decentred market identity is not yet fully realized [it is now]. It occur in educational institutions with a lot of autonomy over the use of the budget and organisation. These aim at attracting students in a competitive environment, meeting external performance criteria, attempting to optimise its market position [exactly like Marjon, suitably scaled down] the same goes for a department or groups inside the institutions. Everything depends on the market. There is an unaccountable hierarchical management system operating allegedly technically, and monitoring the distribution of resources according to the effectiveness of local groups. The institutional identity focuses on exchange value of the product in a market, and there is an attempt to maximize inputs' . The focus is short term and extrinsic, vocational rather than based on exploring knowledge. Flexibility is crucial, so that 'personal commitment and particular dedication of staff and students are regarded as resistances' (69), seen as a restrictive practice. Relations are characterised by contract. Universities themselves might be stratified according to these different identities, with the elite ones able to acquire academic stars to develop the old claims to power and position, with [personal?] identities which can be defined as related to 'introjection [of] knowledge'. In non elite institutions, the organisation becomes 'discursive' as the main way to maintain market positions [that is with flexible discourses to create different packages and permutations]. Identities here work through projection, driven by external forces. We can use the terms in the diagram to recognise the effects of contemporary educational reforms. These have combined centralised control, such as the 'standardisation of knowledge inputs', and local autonomy. Originally, there was a 'complementary relation' (71) between retrospective conservatives and neoliberal marketisers, but also some tension, for example over whether a centralised national curriculum was required - the retrospective seem to have won out here, although there is also an inclusion of basic skills and other 'vocational insertions'. It was the professional pedagogues driving the market identity, with some support from civil servants, although this was not strong enough to completely prevail - for example the original intention for 'complex profiling forms of assessment' ended up with simple tests. Thematic links between traditional subjects were also ineffective [with the same study by Whitty cited again]. The market identity transformed managerial structures and 'has created an enterprise, competitive culture'. It did not affect the curriculum so much, but did introduce 'new discourses of management and economy', say in the training of school head teachers. In other words, it has 'radically transformed the regulative discourse of the institution'. External competitive demands are stronger. This position has been supported by the state. However, contradictions with the more traditional curriculum and the identities it produces have produced 'a new pathological position at work in education: the pedagogic schizoid position'[nice, but it could just be a hybrid, showing the weakness of the original divisions?]. [Why didn't Maton use this term in his piece on cultural studies? Bernstein hints at instrumentalism reconciling or replacing the two in the generic mode in the chapter above] Social change has been described in various ways, including postmodernism and disembedding, but we can use the old terms and compare ascribed with achieved identities. The former have been now considerably weakened, since the classic 'cultural punctuations and specialisation' (72) of 'age, gender, and age relation'[not ethnicity?] have been weakened as bases for identity, in favour of individual achievements. The dimensions of the life space have also contracted, reducing age differences. Those identities achieved through class and occupation have also become weaker resources, even though equal distributions remain. Geographic movements of population also create new sets of cultural pressures. Overall, there has been a 'disturbance and disembedding of identities'. The new ones have not just replaced the old ones, but there are emerging identities - again these will be considered as decentred, retrospective, and prospective. The first one relates to local resources oriented to the present, the middle one to the effects of 'grand past narratives', the third one to provide a new recentred identity for the new conditions, sometimes based on selections from the past. Decentred identities produce two types. The first one is instrumental, where identities 'are constructed out of market signifiers'(73) as in consumerism. These can be coherent, but are not stable over time. The politics associated with them is anti centralist. The second one is therapeutic, relying on internal local resources, introjection, based on the self as a personal project, relatively independent of consumerism. 'It is a truly symbolic construction', with an open narrative, partly oppositional. Internal sense making is stressed. Both of these identities are segmented, but the first one is segmented by the market, the second by some notion of personal development. Both are fragile. In the face of breakdown, the instrumental can shift to the retrospective nationalist, and the therapeutic to prospective, but age and context will be important. Retrospective identities draw on narratives of the past for exemplars. Again there are two types. The fundamentalist, which has subsets of its own (religious or nationalist) assumes a stable impervious collective identity, sometimes with 'a strong insulation between the sacred and profane', with suspicions of the corrupt influences of the profane, as in Islamic fundamentalism, or earlier Jewish orthodoxy. These identities find it difficult to be reproduced in the next generation. Age might have an influence, with the young being drawn to the emotional, intense 'interactive participation'(75). The revival of student fraternities in Europe might also provides an example. However, social change may weaken the social basis and produce differences among the young. The elitist retrospective identity is based on access to high culture, offering 'an amalgam of knowledge, sensitivities, manners, of education and upbringing'[similar to Bourdieu]. Education and social networks can overcome upbringing. There are strong classifications and internal hierarchies, but an avoidance of the market 'unlike fundamentalists'[really?]. There is little emphasis on conversion, unlike fundamentalism, since what is required is 'the very long and arduous apprenticeship'. There is less evidence of 'intense solidarities'- and signs of narcissism rather than the superego formations of fundamentalism. When it comes to prospective identities, narrative resources are important as well, but these are 'narratives of becoming' (76), becoming a social category such as 'race, gender or region'[all involve imaginary communities?]. These are individualised, but offer a new basis for social relations, 'a recentring'. They are often 'launched' by social movements are initially evangelist and confrontational, but also have 'strong schismatic tendencies'. They are also focused on the self. They attempt to desocialise themselves from earlier identities, and depend on new group supports for a new forms of economic and political activity. Apparently, 'in the USA, Islamic movements have created a new basis for black identity' leading to new politics and to entrepreneurialism. The becoming can involve a recovery of something which is still potential, but this is productive of heresy and schism, so 'gatekeepers and licencers' become crucial, and there is a constant struggle over 'the construction of authentic becoming'. This identity in particular shows the potential for 'change in the moral imagination' (77). Enlightenment announced universal rights, but the subject became anonymous in the subsequent universalism. Modern moral imagination may be offering the reverse, and thus shrinking, with 'empathy and sympathy… only… offered and received by those who are so licensed'. However, the subject is no longer anonymous. To take a homely example, people who are moderately short may experience themselves as having a spoiled identity and attempt to rediscover an authentic voice based on 'valid scholarship and research', but requiring a licensed member of the group as a spokesman. The new social category can be established, but it is subject to being undermined by 'a more radical agenda', formulated by those who are excessively short. This is 'the first schism and a new shrinking of the moral imagination'. [The endless procession of the oppressed as Maton puts it] Overall, we are experiencing 'the weakening of, and a change of place, of the sacred'. It is no longer central to the collective social base of society supported by overlapping institutions like state, or religion and education. Today, the basis been weakened and 'the sacred now reveals itself in dispersed sites, movement and discourses' in segmented and specialized forms. Instead of talking of cultural fragmentation, however, we can see the diverse local identities as an attempt to pursue these new forms of solidarity through the 'rituals of inwardness' [an exact parallel to the secularisation debate]. Instrumentalism is the exception. This will deepen pedagogic schizophrenia, since there has now emerged 'for the first time a virtually secular, market driven official pedagogic discourse, practice and context, but at the same time, there is a revival of forms of the sacred external to it' (78). This reverses Durkheim's notion of the sites of the sacred and profane, and also challenges Weber on increasing rationalisation, and produces new tensions between pedagogic identity with their associated transmission and acquisition, and local identities. Of course, not all of these new local identities 'are to be welcomed, sponsored or legitimated'. Notes include a definition of pedagogy as 'the sustained process whereby somebody(s) acquires new forms or develops existing forms of conduct, knowledge, practice and criteria from somebody(s) or something deemed to be an appropriate provider and evaluator... We can distinguish between: institutional pedagogy and segmented (informal) pedagogy'. Informal pedagogy is carried out in every day experience by informal providers, it may be tacit or explicit, and the producer may or may not be aware that the transmission is taken place. Informal pedagogy ease tend to be limited to the context or segment, producing 'unrelated competencies'. There is an interaction between informal and explicit forms, governed by framing regulations which produce varieties of voice and message '(what is made manifest, what can be realized)' (79). Sometimes, the acquirer can initiate change in these. Overall identity 'is the outcome of the "voice message" relations'. |