| Notes on:

Guattari, F. (2011) The

Machinic Unconscious. Essays in

Schizoanalysis, translated by Taylor

Adkins. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e) Foreign

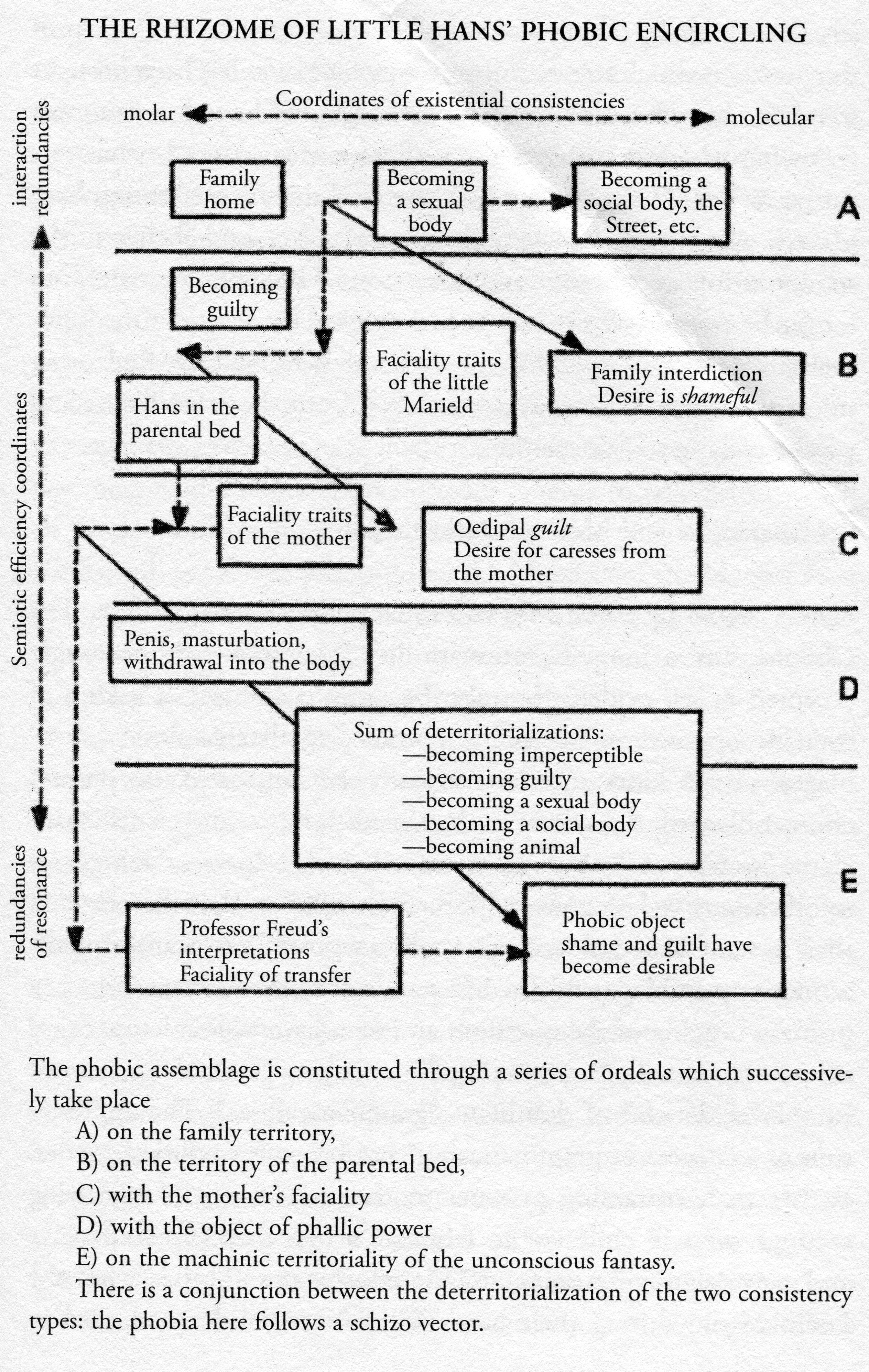

Agents. Dave Harris NB Thanks to Chandler again [Formidably difficult material, as usual. As if the frequent references to offers and discussions that I have not read are not difficult enough, the style is also close to impenetrable, with eternal sentences, and this quality of 'Schizo flow' that others have mentioned. I should be lucky to pick even the most modest bones out of this mushy soup. One thing of interest is that quite a lot of this appears to have been reproduced in Thousand Plateaus,(TP) sometimes almost word for word, like the bit that surrounds the famous statement 'there is no language', page 7 in TP. I suppose the kindest thing that could be said is that this account is slightly more accessible than the pretentious rubbish in TP] Introduction: Logos or abstract machine? [NB see also the discission on machine vs structure in Psychoanlaysis and Transversality] Is the unconscious still a useful concept? Can it still be understood and translated? Modern conceptions see it is a structural matter, with very little left of Freud or Jung, structured like a language, even a mathematical language as in Lacan. For Guattari, the unconscious affects all kinds of perceptions and actions, affecting the possible itself and all forms of communication, not just linguistic ones. He uses the term machinic unconscious to stress that it is full of 'machinisms that lead it to produce and reproduce these images and words' (10). There is a need to reject both classic notions of causality, and structural abstractions. Instead, we need to consider interactions with objects, space and time, without worrying whether they are material, semiotic, or transcendental. We should be working with 'abstract deterritorialized interactions' produced by abstract machines, especially as they traverse different aspects of reality and 'demolish stratifications' (11). These interactions operate on a plane of consistency which crosses place and time. They should be grasped as the 'quanta of possibles'. Assemblages fix and unfix 'coordinates of existence', constantly deterritorializing and singularizing, and establishing new replacement territories—'machinic territorialities'. These processes are universal, and are only slowed down or thickened on the '"normal" human scale'. The same goes for normal understandings of causality and temporal sequence. [Thom is cited on the apparent smoothing or reversability of space and time. Machines are not just understood in terms of their current manifestations and they produce a plane of consistency enabling all sorts of other intersections. Thom is on to this, but too likely to understand it in terms of mathematics, thus remaining at the abstract level, unable to talk about the process of singularization, which Guattari here refers to as 'extracts' from the cosmos and history]. Referring to abstract machines reminds us that we are not just talking about normal processes of abstraction to get to universals, and the need to think of mechanisms as well as assemblages. There are no universal general assemblages—universality is a function of power. The search for some systematic formal order, over expressions, for example, as studied in the social sciences is impossible, because it really depends on 'political and micro political power struggles' to attempt to stabilize an essentially drifting language. Attempts to reduce behaviour and language to binaries or digits could be extended to all social phenomena, but we will not have grasped the essence of the phenomena, unless we make some assumptions that everything aims towards stabilized equilibrium. Structuralism attempts to deal with contingency and singularity by probabalizing them along synchronic and diachronic axes, but this is only a tidying up, and it misses altogether those assemblages that produce 'rupture and innovation'(13). The tendency to aim at general axioms in science, and at pure concepts in philosophy, has meant the dominance of epistemology. The efforts to connect certain privileged denunciations with a transcendent order should be understood instead as a form of power, justifying 'the social status and the imaginary security of its pundits and scribes in the fields of ideology and science' (14). It's possible to develop a formalism operating with 'transcendent universal forms cut off from from history', or to see 'social formations and material assemblages' as embodying them so that they can be inferred. Some encodings will come to appear to be natural, and accidental connections with 'sign machines' will appear as general laws. These were sometimes misunderstood as comprising a metalanguage—but language, enunciation, states of affairs and subjective states are really all on the same level ['flat ontology'] . There are no independent subjects or objects— their seeming independence is really an effect of deterritorialization. Abstract machines connect with deterritorialization and this is what produces apparent universal causess, laws, and pre-established orders. It is common to argue that we can never possible to develop abstract conceptions free from 'invasions' from social assemblages or mass media. However, it is 'assemblages of flows and codes' that differentiate form, structure, objects and subjects in general in the first place so these invasions are just specific observable cases (15). Abstract machines do not code existing social stratifications from the outside. What they do is to offer transformations inside a general deterritorialization, by constructing 'an "optional subject"', a kind of focusing of possibilities, 'crystals of the possible' (16). They assemble components in order to affect realizations, never logically or in a law-like way, but contingently, never simply passing, for example from the complex to the simple, and never establishing a systemic hierarchy. For example, the most elementary elements can bring forth new potentialities and invade more complex assemblages. We need to lose terms like 'the elementary' when describing what goes on and refer instead to a 'molecular level', and this can never be simplified or reduced. Molecules can provide keys or seeds for more complex and differentiated developments. The molecular is more deterritorialized, and this is essential for more complex assemblages to arise. So abstract machines can not be understood in terms of subject and object, nor in standard logical terms [like the subject of a sentence and its predicate?], And nor can they be understood in terms of denotation/representation/signification. Instead, they offer something more general, 'the order of subjectivity and representation, but not in the traditional form of individual subjects and statements detached from their context' (17). One consequence is to move away from anthropocentric conceptions, to move from, for example, logical propositions to 'machinic propositions' and to examine 'non - semiologically formed matter' [eg birdsong]. This will make [conventional, human] coding or signifying look more contingent. There will also be an emphasis on singularity as something that does not just contain 'a limited number of universal capacities'. Assemblages can be undone to reveal other possibilities, overcoming the alliance between universal thought and 'respect to an established order'. Linguistics and semiology claim a privileged place by claiming to be able to solve problems in other disciplines. But this is really a matter of high status and an appearance of scientificity. Saussure, for example, has simply borrowed by lots of psychoanalysts, following some sort of tacit agreement over boundaries of domains. It is this 'shared problematic' that will be investigated in particular (18). Instead, it is important to look at issues which will help us revive the notion of the unconscious, and understand pragmatics in a new way. We also want to look at two particular issues: 'faciality traits and refrains'. Then we want to develop 'a schizoanalytical pragmatics' to address political and micro political problems, and then to go on to develop new semiotic entities based on pragmatics in the form of 'a "machinic genealogy"'. Then we will talk about faciality traits and refrains in Proust [see my summary --sic-- here . See also Deleuze's commentary on Proust] A glossary might help [ha!] In order to replace formal analysis with analytical pragmatics and schizoanalysis, we need to replace a tree with a rhizome or lattice. Instead of dichotomous choices, as in Chomsky, rhizomes can connect any point to any other point. Each semiotic chain can refer to a number of 'encoding modes: biological, political, economic chains, etc.' (19), meaning we can discuss sign regimes and also forms of non signs. We will look at the relations between segments at different levels inside each semiotic stratum, in order to demonstrate 'lines of flight of deterritorialization'. We will emphasize pragmatics rather than underlying structure, machinic unconscious rather than the psychoanalytic unconscious, something that resembles a map rather than 'a representational unconscious crystallized in codified complexes and repartitioned on a genetic axis': this map will be 'detachable, connectable, reversible, and modifiable'. Tree structures can appear within rhizomes, and conversely the branches of the tree can send out buds in a rhizomatic form [but we need a 'pure' model?] We can consider pragmatics as having different components.

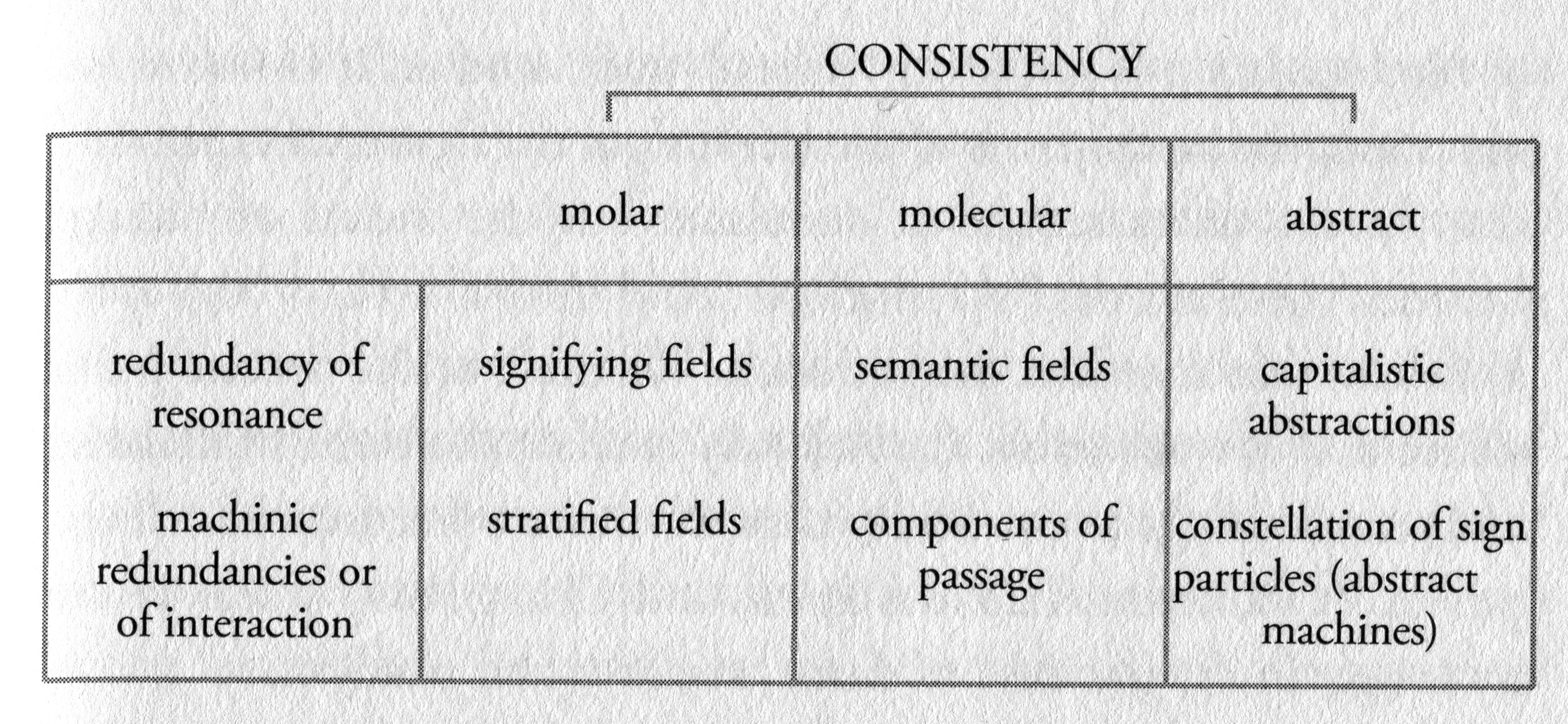

At the semiotic level, there are also two types of redundancy. One involves 'redundancies of resonance'[and this is something to do with faciality and refrains] (21). A second type is machinic redundancies' 'or redundancies of interaction' [something to do with diagrammatic components, presumably the ways in which one gives place to another within the overall diagram? As in evolution through the machinic phylum? OR, the condensed versions of language in 'restricted codes' or ideologies?]. At the existential level, there are three levels of consistency. The first one is molar consistency, relating to 'strata, significations, and realities', and this seems to have to do with phenomena as [collectively?] perceived, including whether or not they are seen as complete objects, subjects or individuals. The second one is molecular consistency, relating to assemblages and how machines are embodied in them. The third one is abstract consistency that apparently 'specifies the "theoretical" degree of possibility of the two preceding consistencies'. by combining semiotic and existential types, we can get 'six types of fields of resonance and fields of interaction'[up to now I had blamed Deleuze for this obsessive classification and tabulation]. The first note refers to differences in terminology, especially with Chomsky, and the second one distinguishes semiology from semiotics. Semiology is 'the translinguistic discipline that examines sign systems in connection with the laws of language', with Barthes as the example, while semiotics proposes to study sign systems 'according to a [pragmatic?] method which does not depend on linguistics', and the example is Peirce. Chapter two. Escaping from Language [Lots of stuff here about different linguistic theories. The main points seems to be to argue that pragmatics is far more important than any other aspect of language, and that general theories, including structuralism, are really describing particular clusters of pragmatic utterances, some of which come to seem important for political reasons] Functionalist accounts of language operated with phonological chains organized around binaries. Language was seen in terms of information theory, with messages and redundancy and so on. Social and political context were ignored, so that linguistics can appear to be scientific and 'serious'. Generative linguistics, as in Chomsky, saw functionalist models as describing only the surface activity produced by underlying syntactic structures. Some followers wanted to describe the syntax in terms of mathematics or types of logic. Even a more recent emphasis on enunciation [Foucault? Someone else I think] has failed to grasp the social and political context, and it is still common to study enunciation in general, or something abstract, 'an alienated enunciation' (24). In all these approaches, pragmatics were seen as something to be dumped in a waste basket, either ignored, or grasped in 'a restrictive mode'. Syntax and phonology dominated. Enunciations were supposed to be located at particular 'structural junctions', but were never seen as contingent or singular. Language was just assumed to be able to represent a social system. It was also assumed that semantic and pragmatic fields could be digitalized—relying on contents and context as something that can be formalized and seen as the result of a 'system of universals'(25). Sometimes this means that semantic creativity depends entirely on syntactic structures [Guattari wants to suggest instead Hjelmslev's notions that, apparently creativity finds an origin in 'the concatenation of figures of expression and figures of contents' -see below]. Generally, creativity is seen as something marginal or deviant, but this does not explain how originally marginal words become mainstream. Linguistics claims to be able to explain all domains that use language, and this makes it 'imperialist'. There are claims to be able to explain pragmatics in a neutral way, as something secondary. Guattari wants to explain pragmatic contents in terms of 'collective assemblages of enunciation'(26). This means that 'there is no language in itself', that what we have is specific language of all kinds being produced via 'an abstract machinic phylum'. There is no direct connection with social structures, and no general structure that produces statements separately. We can start with the classic distinction between language and speech [and deny it in favour of a pragmatics of enunciation]. The pragmatics of the unconscious or schizoanalysis will be particularly hostile to Saussurian structuralism, since it shows that language does not have 'a domain of its own'(27), that it is always an open system connected to 'all the other modes of semiotization'. It is only political or micro political processes that close it up and call it a national language or dialect, or delirium. Language is suffused with 'borrowings, amalgamations agglutinations, misunderstandings'. The same goes for anthropological structures, such as the prohibition on incest, which, when examined in detail, consist of 'rules that can be bent in all kinds of ways'. It is power formations and power centres that unify languages and establish boundaries [leading to the bit that reappears in Thousand Plateaus. The whole discussion on language is very similar in fact -- maybe a bit clearer]. Guattari the recycler:

Note 4, p.333 says: 'Although I wrote them alone, these essays are inseparable from the work that Gilles Deleuze and I have carried out together for many years. This is why, when I am brought to speak in the first person, it will be indifferently with that of the singular or plural. Let one not see there especially the business of paternity relating to the ideas which are advanced here. There as well as here it is all a question of "collective assemblages". Cf. Our book in collaboration: A Thousand Plateaus...' Individuals are always moving from one language to another, using suitable language for a father, for a lover, for a dream and so on. These utterances display a ' whole ensemble of semantic, syntactic, phonological and prosodic dimensions… [As well as]… poetic, stylistic, rhetorical, and micro political dimensions'. Linguistic mutations appear from these languages, as a matter of frequency of use [unstructured by social orders, that is, unlike the examples above?]. The eternal distinction between synchrony and diachrony is also suspect. As with other formalizations, linguists claim an authority by claiming to see abstract linguistic competence behind actual performances. But there is no general structural competence. Languages reflect heterogeneous social and political assemblages, as 'carriers of ... indecomposable historical singularities' (29). The same can be said about structural analysis in chemistry, biology, economics or psychoanalysis. There are no universals in transcendental form, but only 'abstract machines that differentiate themselves, on the basis of the plane of consistency of all possibles' at particular points of the machinic phylum. What are these abstract machinisms? We can get some ideas from early Chomsky, as long as we abandon the later idea of universal syntax, and notions of depth and surface. We might begin by analyzing minor languages, including those associated with children or slum dwellers. We begin to get an idea of the 'linguistics of desire', but this will not be grasped by formalization [and Chomsky is singled out in particular for developing a topology as a tree structure, as his system developed and was codified]. If we return to the earlier model, we can reconsider grammaticality as 'one of the modalities of the abstract power set into play by the most decoded capitalistic flows' (30). We also have to discuss what grammaticality actually means: is it some fundamental axiom producing a generative structure, or is it a 'marker of power and [only] secondarily a syntactic marker' (31)? There is a normative element in it, in that the only normal individuals form grammatically correct sentences, and those who don't are seen as deviant to be 'interpreted, translated, adapted' and sometimes enclosed in institutions. Linguistic competence is seen as neutral and universal, outside of contingency, but it is difficult to think of defining it separately from performance, and thus the concept is always used to judge performance, from a position of power. Chomsky's model does point to the excess of competence and linguistic capacity compared with actual speech or performance, but it is wrong to see this excess [the structure or machine producing excess] as somehow producing performance. It is the other way around, and 'the machine itself is produced by its production'. There is no 'innate faculty'. Competence and performance interact. Thinking of competence as 'the machinic virtuality of expression' can help us deterritorialize rigid statements like stereotypes, or syntaxes, seeing them as tied to a specific social territory, a particular local kind of competence. Alternative competences can sometimes attempt to seize power, as when 'a patois becomes aristocratic, a technical language contaminates vernacular languages, a minor literature takes on a universal importance' (32). These transformations affect 'all the resources of language'. Linguistic competence is not universal, nor are speech acts. They are all associated with networks 'of various semiotic links (perceptive, mimetic, gestural, imagistic thought etc.)'. Statements are produced by 'a mute dance of intensities', operating on social and individual bodies. There might be some relatively universal features [one is ' the morpho-phonological organization known as double articulation']. It is obvious that power formations constitute particular fields of representation, however, often in an overcoded manner, displaying 'contingent relations between heterogeneous layers' (33). Speech acts, especially Habermas's version, have been studied by modern linguistics in opposition to Chomsky and systematic competence: the latter is seen as arising contingently out of speech acts, which are regulated by individual, social, linguistic, and psychological factors [apparently associated with somebody called Brekle]. This is a step towards analyzing real speech acts concretely, which would mean an abandonment of dichotomous or mathematical structures, but we still have an assumption of universality—as in Habermas and universal pragmatics . It would be quite some project to identify these in every speech act and in every possible one! Habermas goes on to say that some are institutionalized in cultures or societies, and this has led some people to identify particular characteristics as more likely to be universal [a list on page 34]. This must be arbitrary, however, and again focuses on normal adult enunciation rather than idiosyncratic performances. We should abandon any attempt to find universals in favour of 'the full acceptance of problematics pertaining to a micro politics of desire and all sorts of macro politics' (35). What sort of power do we find in linguistic fields? Power is not just found in ideological superstructures, and nor is it something that only regulates 'well defined social ensembles'. Power engages 'the whole complex of "extra human" semiotic machines', seen in the power of the ego and superego which make us afraid or neurotic. Combinations of these forms of power can produce stable layers of competence in various activities, including individual semiotic activity, that relating to social machines, machinic forms themselves, and systems connecting domains including ' deterritorializing lines of flight, components of passage, etc.'(36). Making formal distinctions and pursuing abstract foundations of language means we miss the effects of 'collective assemblages of enunciation… The true creative groups concerning languages', and operate instead with either individuated or universal subjectivity. These collective assemblages can indeed display formal or individual qualities, but it would be wrong to turn these into abstract categories. Instead, we need to examine 'the same types of processes of universalization that every power formation has utilized in order to be given the appearance of a legitimacy of divine right', and this particularly applies to expansionist capitalism. We clearly can structuralize and binarize, but it is a mistake to think that we are describing eternal structures, things that have actually produced specific social and cultural forms. Instead it is 'processes of power and machinic mutations' which have produced particular regions of creative potential, and these are the fundamental processes: we can make them more complex, but we cannot decompose them any further. These machines are either connected to assemblages and transform them, or remain virtual. In order to become stable, particular fields have to show themselves to be suitably collective in managing diverse performances, even marginal ones. They have to engage in coding a whole range of 'overflowing' semiotic assemblages, based on 'the dominant mode of semiotization that they set to work' (37), particularly being able to mobilize abstract machines in finance or science, for example. These processes involve 'semiological subjection within fields of resonance' and 'semiotic enslavement within interactive fields of machinic redundancies', or some coordination of the two. We can expect to find dominant grammaticality being imposed, ideological assemblages dealing with content, and 'diagrammatic assemblages of enslavement' operating as referents [the examples are 'flows' of abstract labour as the essence of exchange values, flows of monetary signs as the substance of the expression of capital… Linguistic signs adapted to standardized interhuman communications' (38)]. The intention is to make each individual into a suitable speaker and listener, adopting particular linguistic behaviour that is compatible with capitalist modes of competence. Capitalism has indeed produced a pervasive and direct language that seems natural, operating even at the unconscious level through 'presuppositions, its threats, its methods of intimidation, seduction, and submission'. This makes the search for a new conception of the unconscious particularly urgent. Again we have to deny that capitalist language somehow expresses the apparently fundamental needs or conditions of human beings, and see these instead as 'semiological transformations dependent upon a given context within a power system' (39), with an increasing intolerance towards alternatives. Such language overcodes the signifying machines of the state and its institutions. It replaces 'ancient sedimentary structures' of societies and communities with 'molecular chains of expression'[no doubt in the Hjelmslev sense, to include non linguistic expressions]. Contents appear as necessities, representing dominant opinion and 'the persecuting refrains of the ubiquitous Superego'. Classic forms of desire are detached and transformed into the 'polarity of subject and object', so they can then be attached to social needs. They become inseparable from the significations of mass media, and they become individualized in a fixed, non-nomadic way. We can detect these tendencies in societies before capitalism, and anyway, such societies already showed the existence of less dominant capitalistic flows. However, modern societies, beginning with the middle ages have led to a loss of control over these decoded flows [ones that break with the old symbolic codes]. One result has been 'generalized Baroquism'(40) 'leading to capitalist societies strictly speaking' [so some sort of linguistic determinism? Also detectable in Anti Oedipus]. Capitalism features the 'semiotics and machinic enslavement of the flows of desire', as a response to reterritorialized codes. This is 'correlative' to the emergence of new forms of social division between sexes and ages, divisions of labour, and other forms of 'social segmentarity'. All forms of sense are located in a social hierarchy. There is a constant effort to rethink and modify codes to incorporate 'in detail every significant relation'. Children have to undergo an apprenticeship in the use of such language, including when they become sexualized and socialised. They will encounter, for example a 'regime of pronominality and genders that will axiomatize the subjective positions of feminine alienation'. Again there is no universal or common language between these categories. Any languages claiming to be national, such as 'those spoken in the French Academy or on television' are really metalanguages, preserving social distance with other languages', and forcefully imposing over coding. We need to return to Hjelmslev, but not the bit where he wants to axiomatize language. [Here is a good discussion of this, reducing, for example, narrative form to a series of what looks like Boolean logical connectors]. And try this nice condensed summary in the irreplaceable site on semiotics by Chandler:

However, we can rescue the general notion of semiotics using these terms, and denying the abstract universality of signifier and signified [indeed, in Thousand Plateaus, all sorts of inanimate objects including rock strata are can be seen as offering expressions — I think this is very misleading in practice]. In particular, we should see forms only as expressed by or in substances, including non linguistic ones. [I think the argument here is that nonlinguistic expressions, involving rocks or whatever, are seen as the original form from which linguistic forms have emerged]. We need to consider the nonlinguistic in order to grasp better 'the abstract machinism of language'(42). [The argument might be that we need this abstraction to explain the appearance of semiotics substances of all kinds]. Hjelmslev goes on to argue that we should not see the syntagmatic dimension as a mere product of the system—again, processes are not based on universal codes, but arise from assemblages which support those codes. We also need some 'basic materials' which can be used in the process of expression. The issue is to decide what makes some semiotic components creative, and what might institutionalize them. Again it is pointless to look at the qualities of language itself, since it can produce proliferation, mutations and standardization. Nonlinguistic components are often crucial to break conformity or to 'catalyse mutations' (43). There is no creative potential in the formal units of content. The pragmatic level of enunciation, especially assemblages of enunciation, and molecular matters of expression are where we should look: these bring into play abstract machines. This helps us to break with overcoded languages by going back to assemblages, where standard significations are on offer, supported by hidden power formations. We need to preserve 'this systematic politics of "good semiotic choice"', by going back to assemblages and components that produce 'signs, symbols, indexes, and icons' Chapter three Assemblages of Enunciation, Pragmatic Fields and Transformations [This is very technical and I do not know enough about linguistics to fully follow it. Allow me to present a plain man's gloss. An initial starting point might be the 'semiotic triangle', which connects signs, thoughts and objects in various formulations. Thank goodness for Chandler who provides this:

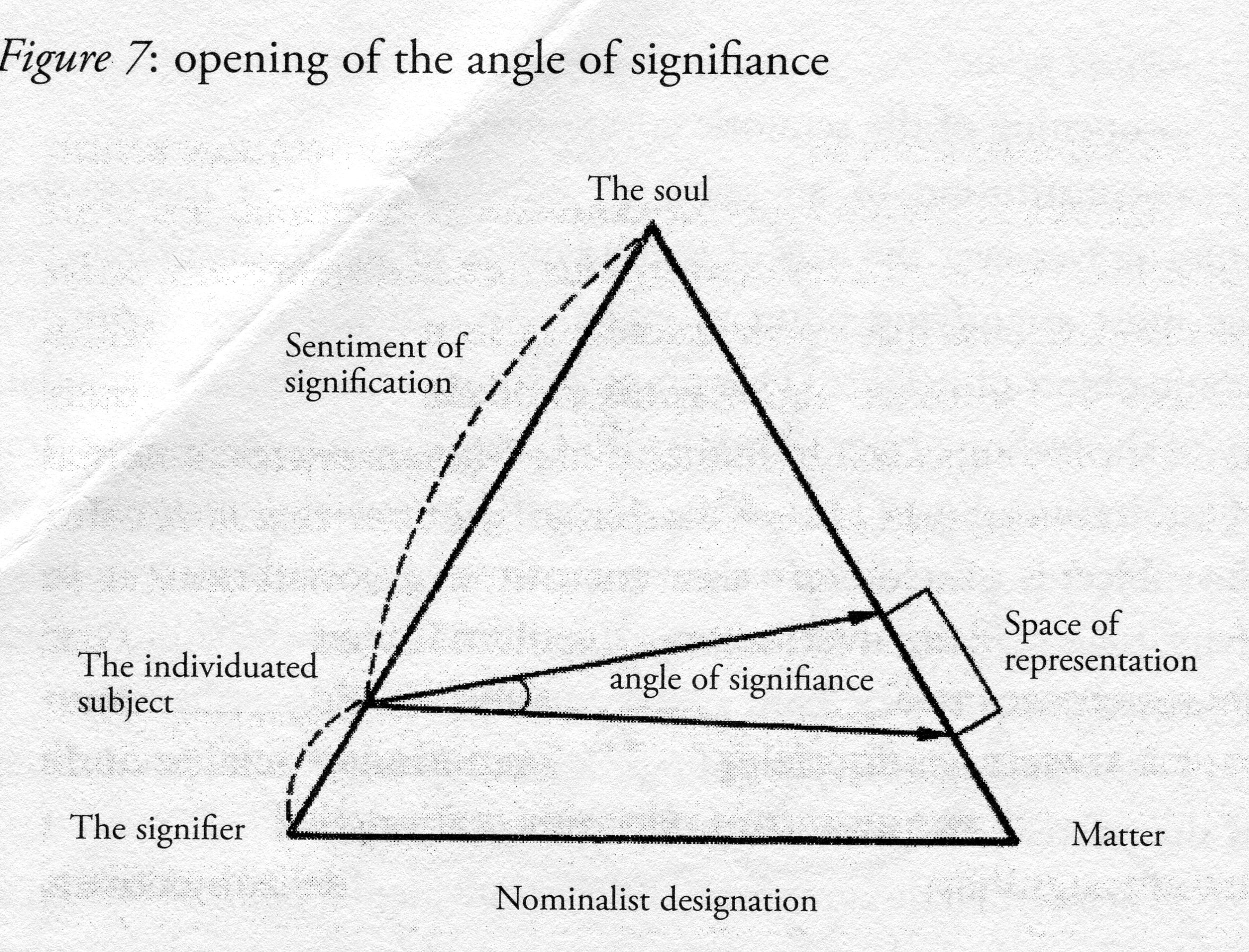

Typically, these components are connected in the form of collective enunciations or assemblages which not only specify the content of the links, so to speak, but also privilege the legitimate ones. Guattari is able to develop this model and add dimensions to it, and then to offer a table of the possible combinations. I'd take this to be the 'diagram' of possible forms of enunciation. The diagram offers machinic variations, as various connections are established between different options, including the mysterious 'resonances'. However, there are mundane variations as well, since each of the points of the triangle can demonstrate change—objects can change as in technological progress, signs can change as languages develop, including developing flexibly to exploring metaphors and analogies and that, and thoughts can change as culture is developed. It is also possible to see how linguistic assemblages are connected to cultural and social assemblages, and this clearly develops on from all the stuff about over coding in Anti Oedipus. Here, Guattari sets up some ideal types societies, including the one taken to be the most primitive form, which looks pretty much like mechanical solidarity in Durkheim. Signs and thoughts are tightly confined by a collective agreement to enunciate in a particular way and to rigorously police any deviations. By contrast, capitalist societies are heavily individuated, with apparent autonomy given to signs and thoughts, although in practice, these are overcoded, that is subjected to dominant meanings expressed over and over in a redundant way. Now read on…] [Not yet...While I am here, the phrase 'redundancy' occurs a lot ,in a linguistic sense, and it normally means repetition so as to convey meaning as in 'overcoding'. However, according to a primer on grammar I found on the web, it can also refer to material that is surplus to identifications of a particular grammatical unit and 'In generative grammar, any language feature that can be predicted on the basis of other language features'. There is also much reliance on 'resonance' as a linking mechanism between components and systems. Too much reliance in my view where it helps Guattari duck out of being more precise about what leads to what. I think of it in terms of DeLanda's dicusssion about how signals, when brought into close association, can line up their wave lengths as they dampen the variations in each other -- this is my take on the normal notion of physical harmonic resonance as in guitar strings etc. However, it must surely be used as a scientific-looking metaphor here, just to explain how all the forces converge in semiology and social and psychological systems to produce the reified capitalist subject. He might as well have said 'pixie dust'. ] Content and expression are attached together in assemblages of enunciation. Originally, before formed up human language, we have only 'components of semiotization, subjectification, conscientialization [see below] , diagrammatism and abstract mechanisms' (45). These are joined by systems of correspondence and translation between language and culture. Some of these appear as common sense, but there are many other possibilities. Assemblages are partially autonomous from 'the plane of content' and their 'angle of signifiance' depends on the conditions of the semiological triangle, a way of '"holding" a given subset of the world'. Note that word 'signifiance' which I am translating in my layperson's way as the capacity to signify or to offer significations. [Massumi's notes on translation and acknowledgements suggests more technical definitions. Signifiance refers to the syntagmatic processes of language, and interpretance to the paradigmatic ones in a '"signifying regime of signs"' (xix). Beneviste, who was the originator of the terms, has his work translated into English thus: '"signifying capacity" and "interpretative capacity"'] The subject itself is not just a result of the play of the signifier, but the product of heterogeneous components, some of which produce meaningful dominant realities. Individuation is itself the result of certain social organizations and the operations of the unconscious, the way it manages 'the libidinal topics of the social field' (46). The notion of subjects, approved contents, and the law are determined by relations of power. There is no universal content, universal world. For example, there are no universal mechanisms of male domination based around the operation of the phallus either—the apparent ubiquity [redundancy] of phallic forms simply shows the effects of particular authoritative institutions and ways of representing persons [which is what I think is meant by 'faciality', but we will come to that]. There is no intention to separate out and isolate assemblages of enunciation and desire. These assemblages can deterritorialize. However, deterritorialized desire can lead to capitalist forms of subjectification, because of the effects of 'semiological subjection and semiotic enslavement'. It will not be easy to pursue deterritorialization in the name of molecular revolution [a note on page 336 explains why—each side of the semiological triangle contains a number of diverse apparatuses and possibilities, and any molecular revolution would have to deal with all of them—including scientific and economic assemblages, ideological apparatuses, and various established 'modes of perceptive encoding', mass media and so on]. The more obviously contingent nature of power relations conceals other attachments to these assemblages. Each assemblage has a 'machinic nucleus', comprised of abstract machines, operating as 'crystallization of a possible between states of affairs and states of signs' (47)—like those mysterious virtual particles in contemporary physics, it is useful just to presuppose their existence. Abstract machines produce 'redundancies of resonance (signification) or redundancies of interaction ("real" existence)', depending on whether they are fully embodied 'in a semiological substance' or exist only [virtually] on a machinic phylum. Abstract machines like this display three types of consistency:

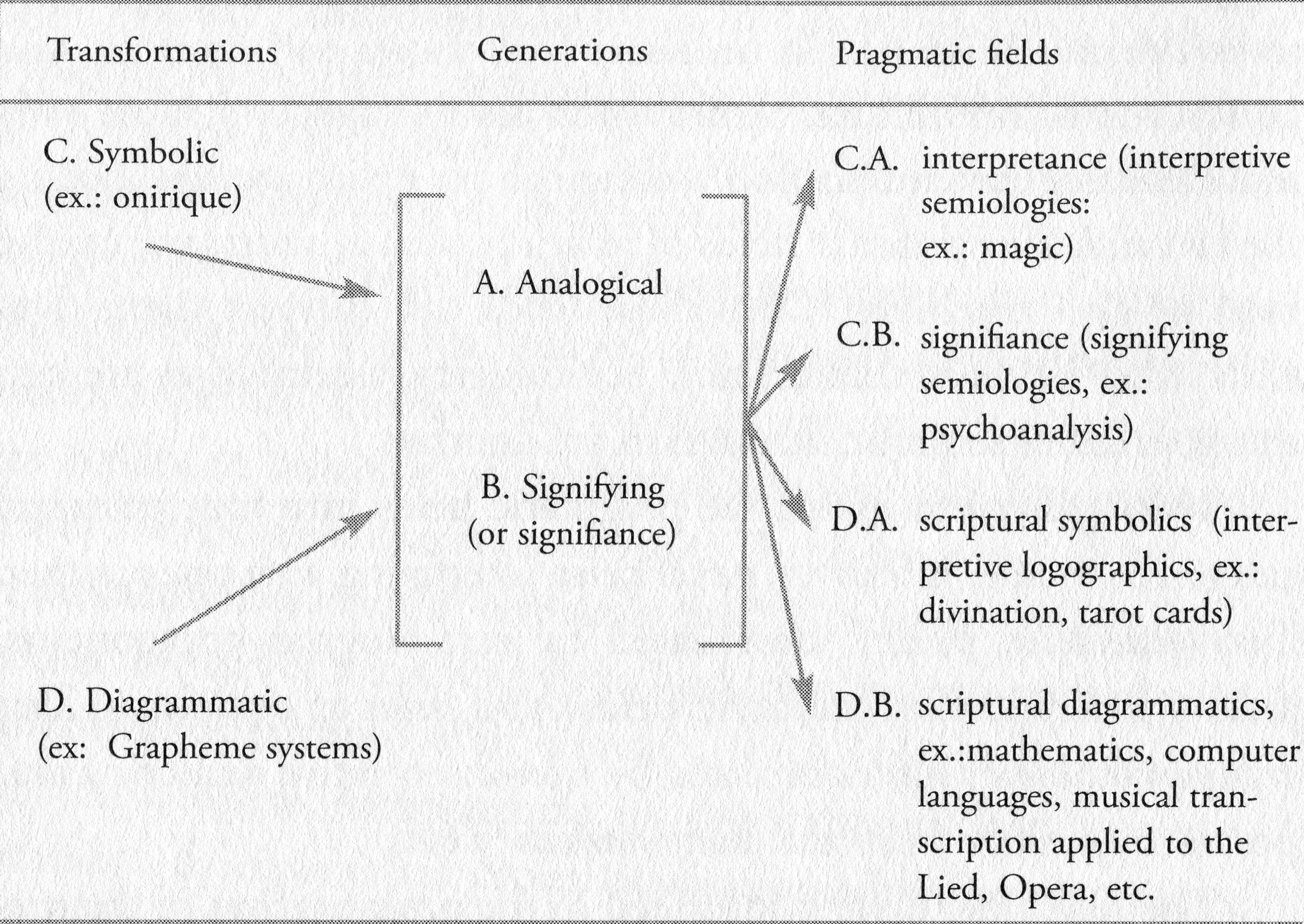

Combining the molar and molecular and the abstract types of consistency with the notions of redundancies of resonance and interaction, provides the six cell table (51) (see below). These types of fields are interrelated and dynamic. Some can 'swell' until they are totally redundant or powerless [cells in the second column?], asignifying components can develop from signifying ones, and pure abstraction is never possible [bottom right cell,column 4], even with computers which always retain 'some semiological terminals that are human'.  We can see what happens in these interacting assemblages by looking first at those that express capitalistic power. Capitalism develops 'a world of simulacra' from semiological redundancies. It is the passage between referents, expressions, and representations that produce these simulacra. This process even 'simulates diagrammatic relations' (52), but without any critical potential, since it claims to represent the actual world with no room for creative dissent, only its occasional version of 'Life, the Spirit, and Change'. Any abstractions will look synthetic and arbitrary [one example is '"extremist" religious assemblages'], and any other abstractions are likely to be reterritorialized. In particular, subjectivity and objects of desire are framed, by connecting them, through what looks like reasonable resonances, to control mechanisms, such as superegos, exchange values, or 'an imaginary museum'. There is no attempt to connect them to any absolute [as in mechanical solidarity] , but rather to 'coordinated systems of power', which manage lines of flight and lines of dissidence as an example of 'oppression, distancing, autonomization, and alienation from an increasingly domesticated plane of the signifier' (53). The process of homogenization also involves splitting individuated subjects from assemblages of enunciation, the reproduction of conservative signifiers, sometimes drawing upon limited versions of the diagram, and overcoding of speech and writing through the control of syntagms and paradigms. However, there is always a possibility of new kinds of deterritorialization. Capitalistic abstraction therefore operates to neutralize and recuperate lines of flight and machinic possibilities ['machinic indexes'], and is linked to particular institutions. Religion is one, but now there are more fragmented and diversified mechanisms including 'public infrastructures and facilities' and the mass media. Together, these produce 'a gigantic net, composed of points of potential signification', and it is impossible to escape, because all assemblages of enunciation are woven in. There is a constant alteration and recalculation so that the 'thresholds of deterritorialization' are always trimmed for the established order and made coherent. Lines of flight will be confined within this horizon, and machinic assemblages will have to deal with contents that appear to be universal. [Sounds like an elaborate way to describe hegemony]. If we turn to Hjelmslev, we avoid the simplifications of signifiers and signified, and we can extend the notion of content and expression 'to all the various assemblages of enunciation' (54). There is more to 'semantic reality' than just signification. Semantic fields refer to particular operations, particular transformations—'analogical interpretations' these involve redundancies of resonance and interaction. Particular assemblages can be derived from signifiation processes or 'diagrammatism', and all actual assemblages affecting humans are mixed. Possibilities are closed off by power and an emphasis on the subject [the 'personological pole'], but there is always a potential for new possibilities, since abstract machines always exceed any apparently 'fixed and universal coordinates' (55). We can build on the pragmatic component suggested in the Introduction to produce 'four general types of mixed assemblages of enunciation'[sigh]. Everything depends on how content is provided: